Why Josef Prusa keeps chasing competitors instead of innovating

by Kai Ochsen

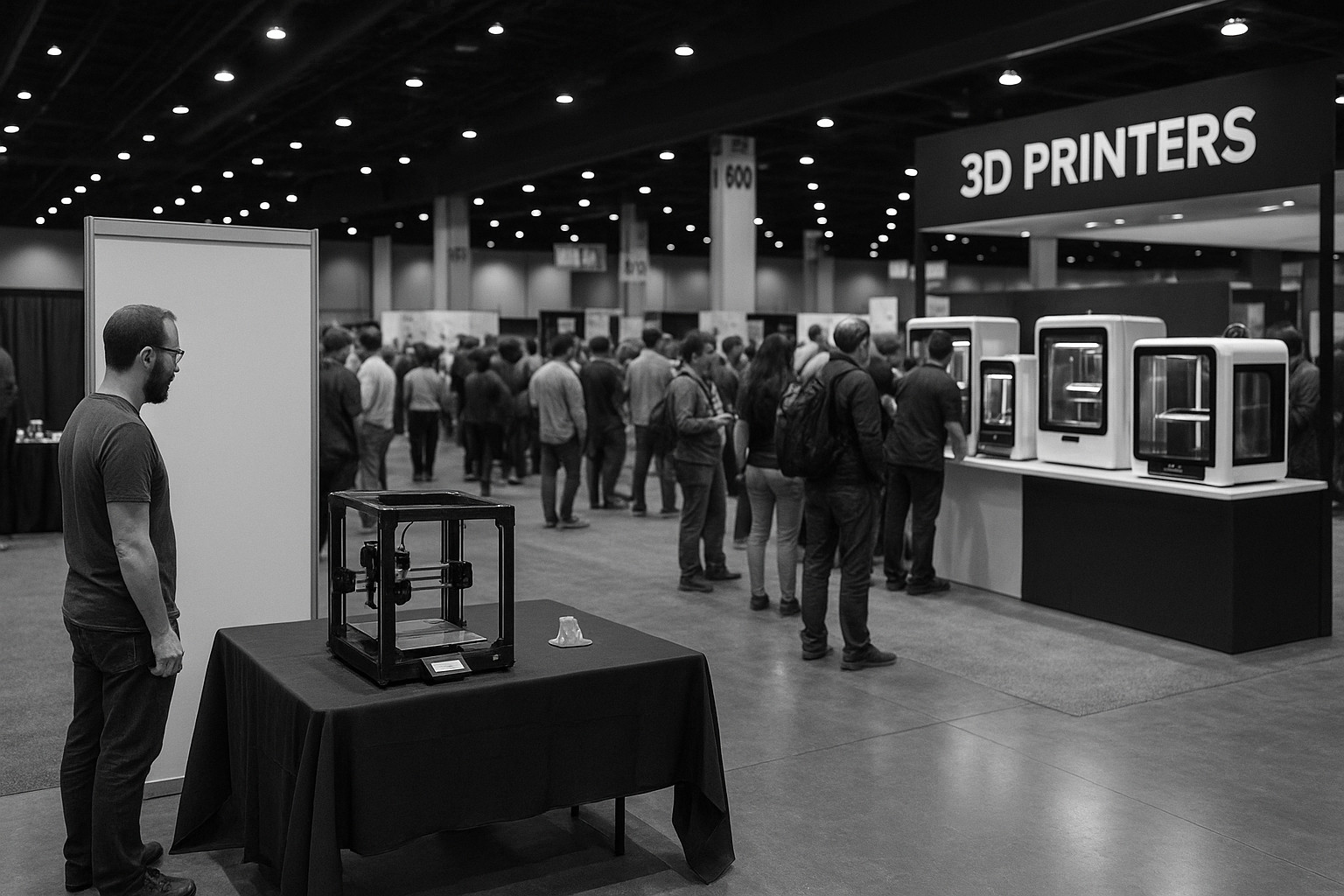

Few topics in 3D printing generate as much fatigue as Josef Prusa. His name once symbolized creativity, open hardware, and grassroots engineering. Now it triggers a different reaction: resignation. Many hoped the story would change, that lessons would be learned, that time would bring maturity. Instead, the same pattern repeats. Announcements appear suddenly after competitors speak. New products look like old ones stretched into new shapes. Problems that should have vanished years ago remain stubbornly present. The latest example arrived with the reveal of the Prusa Core One L. Presented at a carefully curated event, the machine was unveiled as though it were the company’s next heroic leap. But anyone following the industry could see a different picture. The Core One L resembled a scaled-up version of an earlier model rather than genuine progress. Its timing was no accident. The announcement came suspiciously soon after Bambu Lab revealed its new P2S, a thoughtful evolution of its earlier P1S that actually introduced improvements users had requested.

This pattern has become familiar. Prusa follows, rather than leads. When Bambu introduces something, Prusa responds. When competitors deliver innovation, Prusa stages a presentation. The gap widens each year. What once felt like pioneering spirit now resembles a scramble to remain relevant. The timing of announcements makes this plain. Some arrive before products are even finished, as if the message matters more than the machine. The performance overshadows the engineering.

Quality has not kept pace either. Despite their premium price, Prusa machines continue to exhibit issues surprising for a brand with so much experience. PETG parts with tolerance problems, VFA artifacts that no longer shock anyone, and electronics that fail in ways that render machines unusable. A single faulty bed cell can disable an entire MK4. USB ports malfunction. Even the expensive XL suffers from problems that users should never face at this price point. These issues might be less troubling if they were isolated. They are not. They form a pattern. Problems appear, linger, and recur. Support replies slowly, if at all. Customers outside Europe endure high shipping costs, import duties, and delays when seeking repairs. The result is a machine that costs more to acquire and more to maintain, and still fails to deliver the consistency users expect. A premium price without a premium experience leaves frustration, not loyalty.

Meanwhile, the world has changed. The maker era that shaped Prusa’s identity has faded. Hobbyists still exist, but they are no longer the mainstream audience. Most users simply want a 3D printer that works. They want to unbox it, power it on, and start printing. They do not want to rebuild it like a piece of furniture. They do not want to diagnose errors they never caused. The machine is supposed to serve them, not the other way around. Chinese manufacturers, whatever their flaws, understood this. They delivered plug-and-play machines with thoughtful ecosystems: cameras, calibration systems, mobile apps, and cloud workflows. They built a complete experience. Their products targeted people who value time more than tinkering. The message was simple: create, not troubleshoot. While others moved forward, Prusa remained loyal to a process that once made sense but no longer fits the world around it.

This shift reveals a deeper truth. The conflict is not just technical. It is cultural. Prusa’s identity is rooted in the past. It embraces handcrafted parts, manual assembly, and a narrow sales channel that forces customers to navigate international shipping and limited support. For a time, these quirks signaled authenticity. Now they signal stubbornness. The broader market has evolved, but Prusa has not. Nostalgia became a cage.

Some still defend the company. Loyalty is powerful, especially when built over years of engagement and open development. But loyalty cannot blind reality. The competition offers better performance, better reliability, and better value. Innovation is moving elsewhere. The conversation has changed. Even those who admired Prusa now see that sentiment cannot compensate for stagnation. The industry listened, adapted, and moved; Prusa stayed still. The result is a story that no longer surprises. The disappointment feels routine. A company born from imagination now trails behind those who imagined more. The tragedy is not that others surpassed Prusa. That is the nature of progress. The tragedy is that Prusa did not try to keep pace.

A launch overshadowed by others

Product launches usually celebrate accomplishment. They mark the moment when years of development coalesce into something new. But the debut of the Prusa Core One L felt different. It arrived quietly, yet theatrically, as if the spectacle mattered more than the engineering itself. A handful of industry personalities were invited, many already sympathetic to the brand. The event looked polished, yet beneath the presentation lay an uncomfortable truth: the announcement was a reaction, not a milestone. Only days earlier, Bambu Lab had introduced the P2S, a logical successor to the P1S. The update offered refinements that answered real user needs. Better performance, better system integration, more cohesive software. It felt like evolution. When Prusa spoke, however, the message lacked that sense of progression. The Core One L looked like a machine created simply to appear bigger than the MK4, not better. The timing made the comparison unavoidable.

Veterans of the 3D printing world recognized the pattern immediately. Prusa does not lead the conversation anymore. It responds to it. The Core One L announcement mirrored the scramble seen during the introduction of the MK4, when promises preceded delivery and the product existed more in theory than in practice. This latest reveal had the same energy: a preview designed to maintain relevance rather than demonstrate advancement. The reveal mattered more than the machine.

Specifications highlighted size but offered little else. No transformative features, no ecosystem changes, no step forward that addressed long-standing concerns. Users waited to hear about improvements in reliability, calibration, surface quality, or airflow management. Instead, they saw a scaled frame and familiar hardware choices. The story was breadth rather than depth. In an industry driven by innovation, that is not enough. Those who attended applauded politely. Many in the audience were long-time supporters, influencers who owed their visibility to years of collaboration with the brand. Their excitement felt insulated from the reality unfolding elsewhere. While they celebrated, users outside the room compared notes and wondered why the announcement felt thin. Bambu’s reveal had substance; Prusa’s offered size.

For customers, especially those abroad, the moment highlighted a broader frustration. The release of new hardware that does not meaningfully improve the experience feels disconnected from the realities of ownership. People face support delays, shipping barriers, and ongoing hardware quirks. A new model that fails to address any of this looks indifferent. Instead of solving problems, Prusa seemed intent on proving presence.

The muted response from the community said more than the applause inside the room. Social channels filled with cautious interest but few endorsements. Discussions quickly shifted back to the P2S, to its new features and integrations. The Core One L announcement became a footnote. It had not reshaped expectations or excited imaginations. It had simply filled space. The most telling detail was not what Prusa said, but what it did not. There was no acknowledgment of persistent issues. No attempt to explain how the Core One L would exceed the performance of machines that cost far less. No roadmap that suggested a shift in priorities. The message was clear: growth meant scale, not refinement. The community heard that message and quietly moved on. A launch should signal direction. The Core One L signaled hesitation. It showed a company caught between nostalgia and necessity, unsure whether to evolve or repeat itself. In a marketplace defined by aggressive innovation, that indecision is difficult to ignore.

Imitation without evolution

The Core One L could have been an opportunity. A chance to restore confidence, to demonstrate that Prusa could still challenge the direction of the industry. Instead, it reaffirmed the impression that the company is reacting to its competitors rather than charting a path of its own. The machine’s defining feature is simply its size. Growth by volume is not innovation. It is repetition at scale.

Bambu Lab’s P2S did not reinvent 3D printing, but it advanced it. Users saw thoughtful upgrades. Better materials, improved calibration logic, and tighter coordination between hardware, firmware, and cloud services. Small changes combined to create a smoother, more cohesive experience. It looked like the product of iteration guided by user feedback, not a scramble to claim relevance. That difference revealed a gulf that size alone cannot bridge.

The Core One L feels like an answer to a question no one asked. Users did not request a taller MK4 with similar limitations. They asked for reliability, refined motion systems, quieter operation, and modern features. They asked for cameras, sensors, and integration that reflected contemporary expectations. They wanted a platform that acknowledged the last three years of progress. What they received instead was familiar hardware in new proportions, a gesture rather than a step. Even the marketing language hinted at uncertainty. There was no clear narrative about what this printer solves beyond capacity. No explanation of how it improves quality, reduces failures, or supports automation. It looked less like an evolution of the MK series and more like a stretched concept released under pressure. The silence around practical benefits spoke louder than any press image.

This approach repeats a broader trend. When Bambu introduced its AMS system, Prusa hinted at future plans. When Bambu delivered remote monitoring, Prusa promised improvements someday. When multi-material solutions emerged from Chinese competitors, Prusa responded not with engineering, but with licensing agreements. The message is consistent: innovate by association rather than creation. Buying technology replaces building it. The INDX multi-head development, sourced through Bondtech, illustrates this clearly. Rather than designing a system internally, Prusa partnered to secure access to technology others were already preparing. There is nothing wrong with collaboration, but collaboration without foundational direction becomes dependence. If the cornerstone of your next flagship offering belongs to someone else, what does that say about your role in the process?

Meanwhile, other brands iterate quickly because they are willing to reconsider first principles. They discard systems that have reached their limits, replacing them with cleaner, more efficient architectures. They choose integration over patchwork. That is why their products feel modern. They are not shaped by legacy design choices. They were built for today’s expectations. Prusa remains anchored to yesterday. Users feel this stagnation. They recognize that the Core One L does not open new possibilities. It simply allows the same machine to print bigger objects. Few will notice a transformative difference in performance, precision, or workflow. The printer’s story ends where it begins: it is larger. Everything else feels unchanged.

In an industry where innovation is not optional, imitation without evolution reads as surrender. The Core One L could have shown that Prusa still had vision. Instead, it confirmed that the company is tracing footsteps left by others, hoping that presence alone will suffice.

Quality control that never matures

Quality should improve with experience. More years in the market should mean tighter tolerances, better sourcing, and more reliable design. But Prusa machines continue to demonstrate the opposite. Problems that should have disappeared by the third or fourth product generation remain visible in the latest models. Each new release carries familiar flaws, as if the company has learned nothing from its own history.

One of the most persistent issues involves PETG components. These printed parts remain central to Prusa construction, even in expensive models like the MK4 and XL. PETG offers convenience for rapid prototyping, but it introduces weak tolerances and inconsistent mechanical behavior. Temperature fluctuations, assembly pressure, and extended use can deform these parts over time. Customers paying premium prices do not expect structural elements that look like hobby outputs. A flagship machine built from printed brackets feels unfinished. VFA artifacts are another recurring problem. Vertical Fine Artifacts have followed Prusa machines for years, appearing across models and revisions. Community discussions have produced theories, workarounds, and firmware tweaks, but the issue persists. It is no longer an occasional blemish. It is a characteristic. Users now treat VFA as an accepted limitation rather than an engineering failure that should have been solved. That normalization says more about the company’s priorities than its capabilities.

Electronics have not fared better. Reports of failing bed cells on the MK4 reveal a fragile system where a single defect can disable the entire printer. If the failure occurs in a region the firmware cannot ignore, the machine becomes unusable. Owners must replace expensive components rather than repair isolated zones. The logic of the design offers precision while surrendering resilience. When one pixel breaks, the whole screen goes black. Other components have shown similar instability. USB ports that intermittently fail, power issues that appear randomly, and boards that lose reliability over time all contribute to a sense of fragility. These are not rare events. They form a pattern documented across forums and user communities. Owners who expected reliability encounter uncertainty instead, especially when failures occur outside Europe, where repair is slow and costly.

The Prusa XL exemplifies how scale compounds problems rather than solving them. This premium machine, costing well over four thousand dollars, still suffers from issues that should not exist at this level. Assembly defects, calibration anomalies, and motion inaccuracies appear too frequently to be dismissed as isolated incidents. For many, the XL feels like a prototype sold at retail price. The gap between cost and consistency widens rather than shrinks. None of this means that every Prusa machine fails. Many users print successfully for years. But reliability should not depend on luck. A well-engineered product should deliver predictable behavior across units and regions. Consistency is the result of controlled processes, not favorable odds. When customers wonder whether their new machine will be “one of the good ones”, the brand has already failed its responsibility.

Perhaps the most revealing detail is how long these issues have remained unresolved. They are not new discoveries. Enthusiasts have discussed them for years, offering data, analyses, and suggestions. Yet the same defects appear in new models and updates. That repetition suggests a reluctance to redesign, an attachment to familiar methods even when those methods no longer meet the needs of modern users. Progress stalls when tradition outweighs evaluation.

Quality control is not only about eliminating defects. It is about shaping confidence. The best companies earn trust through predictable excellence. Prusa once had that trust. Today it feels conditional. Customers buy with hope rather than certainty, assembling machines while wondering which flaw they will discover first. That uncertainty is not compatible with a market that increasingly values reliability above everything else.

When the past becomes a handicap

The early days of Prusa were defined by charm. A small European workshop printing its own components, assembling machines by hand, and publishing designs under open licenses made the brand feel personal and revolutionary. At that time, this approach made sense. The market was young, the maker culture was thriving, and users were willing to tinker. A 3D printer felt like a project as much as a tool. That identity became the foundation of Prusa’s reputation. Over a decade later, the company continues to operate under the same assumptions, but the environment around it has changed. What once felt authentic now feels outdated. Printed PETG parts remain central to the construction of its machines, not because they are the best option, but because they preserve a legacy image. This stubborn attachment to tradition has become a technical and commercial burden. The workshop aesthetic that once inspired confidence now signals limitation.

Hand assembly might still appeal to a shrinking niche, but it is fundamentally incompatible with scale, precision, and global reliability. Every unit becomes a variation of human labor rather than a tightly controlled product. The result is inconsistency. Some machines arrive perfectly tuned; others require immediate troubleshooting. The experience depends more on which employee happened to assemble it than on design repeatability. Consumers paying premium prices do not seek artisanal variance. They expect uniform performance.

This devotion to heritage obscures opportunities for improvement. Standardizing components, eliminating printed parts, and relying on modern manufacturing would solve many lingering quality issues. But adopting these methods would also mean abandoning the image that made Prusa famous. Nostalgia becomes a corporate strategy, even when it hinders progress. The company continues to present manual assembly and Haribo gummy candies as a virtue, though it increasingly resembles an excuse. The consequences are most visible when compared with newer competitors. Brands like Bambu Lab embraced industrial workflows from the start. Their machines arrive fully assembled, calibrated, and prepared for immediate use. They do not ask customers to become part of the manufacturing chain. They simply deliver. In that context, Prusa’s approach feels like a relic of a different era, one where hobbyists accepted unfinished products and took pride in completing them.

Some still romanticize this process. They call it “learning”, “community”, or “the maker spirit”. But most users today want ideas, not rituals. They want to design parts, prototype quickly, and iterate without constantly adjusting hardware. The machine is supposed to be a tool, not a teacher. When an ecosystem asks users to spend more time fixing than creating, the tool becomes an obstacle. International customers feel the weight of this heritage even more. Assemblies built by hand are vulnerable to damage in shipping, inconsistencies in calibration, and unpredictable wear. When issues arise, distance amplifies the difficulty. Sending machines back for service becomes expensive, slow, and uncertain. The charm of hand-built construction evaporates when the nearest support center is across an ocean.

Clinging to past identity also limits technological ambition. While others experiment with new sensing, motion, and calibration systems, Prusa seems content to refine the same framework. Improvements come slowly, and usually through small incremental changes rather than bold rethinking. The company behaves like a craftsman in a world that now demands engineering. Its core philosophy has not adapted to the scale of modern expectations.

The past is valuable only when it guides evolution. When it becomes a shield against change, it turns into a trap. Prusa continues to celebrate the methods that once defined its success, unable or unwilling to recognize that the market has left those methods behind. What was once a competitive advantage has become a self-imposed restraint. The company remains loyal to an era that no longer exists.

The world moved on, Prusa did not

The expectations users once had for 3D printers have changed. A decade ago, hobbyists enjoyed assembling their machines, calibrating parts, tweaking profiles, and solving mechanical issues. It was part of the experience. Many learned electronics and firmware because there was no alternative. A printer was half-finished by design, an invitation to explore. That era came with a sense of excitement, but it also came with low standards. Failures were forgiven because the technology felt new. Today, the landscape is different. People still appreciate understanding their tools, but fewer are willing to invest the time required to build or constantly maintain them. Most simply want their machines to work. They want to unbox, connect, and print. They want predictable behavior and dependable results. They expect professional reliability from consumer devices. The shift is cultural: creation now holds more value than tinkering.

Bambu Lab identified this change and built a business around it. Their machines arrive nearly ready to use, requiring little more than a few screws and basic setup. Calibration happens automatically. Firmware updates are integrated with the cloud ecosystem. Cameras and sensors are standard. The package reflects modern expectations. It does not ask users to learn the machine before they use it. It allows them to focus directly on their work.

Prusa, on the other hand, continues to present assembly and self-maintenance as meaningful parts of ownership. Even pre-assembled printers often require adjustments. Users face loose belts, alignment problems, and early failures. Troubleshooting consumes time better spent designing or producing. For some, this might be acceptable. But for most, it feels like a burden. When competitors offer systems that remove these obstacles, the old approach loses its appeal.

Software has followed the same divide. Integrated platforms now allow users to slice, monitor, and manage their printers remotely through a cohesive interface. Messaging, updates, and analytics are unified. Prusa, despite early moves in this direction, still lacks fully mature infrastructure. Cloud features feel fragmented. Remote interaction is limited. The experience oscillates between legacy design and partially realized modernization. Meanwhile, other brands present systems that feel fluid from end to end.

This gap has widened because the market no longer revolves around hobbyist culture. It revolves around productivity. Small businesses, schools, workshops, and casual users all want reliability at scale. They want to print dozens or hundreds of objects without constant interruption. They do not care whether their frame brackets were printed in PETG. They care whether the brackets hold alignment after months of operation. Practicality outweighs sentiment.

Global logistics reinforce this shift. If a component fails in a Bambu machine, replacement is fast. Multiple regional sellers and distributors handle parts and service. The customer does not need to deal with a single manufacturer in one country. Prusa has not built this network. Its support and fulfillment remain centralized. Buyers outside Europe pay more, wait longer, and navigate customs. The model assumes patience in a world that has little. As expectations rise, Prusa’s value proposition becomes harder to justify. The machines are not the cheapest, nor the fastest, nor the most advanced. Their identity is based on a vision from a market that no longer functions the same way. The company seems unaware that the audience has shifted from hobby builders to makers with deadlines. The machine is supposed to enable creativity, not delay it.

The world moved forward because users demanded more. Bambu and others listened. Prusa did not. The result is a widening separation between what people need and what Prusa offers. The brand that once embodied progress now feels like a memory, preserved rather than reimagined.

Isolation makes everything worse

Buying a Prusa printer outside Europe is an exercise in patience. The customer has no choice but to purchase directly through the company’s website or, in some regions, through a reseller who often charges an even higher price. This limited distribution network feels outdated in a global market where competitors sell through multiple channels and maintain regional support hubs. The experience begins with friction and rarely improves afterward. Import duties and shipping costs add another layer of frustration. Customers in the United States, South America, and Asia routinely pay premiums that push already expensive machines into luxury territory. Once the printer arrives, any failure becomes a logistical puzzle. Returning a unit for service means repackaging the machine, paying for shipping, negotiating customs again, and waiting weeks. Ownership feels more like stewardship than use. Support does exist, but response times vary, and resolutions often depend on where the customer lives. For those far from the Czech Republic, troubleshooting becomes a prolonged exchange of messages rather than direct service. Replacement parts might take days or weeks to arrive. Meanwhile, the printer sits idle. Users who rely on their machines professionally face real costs. A premium product should not require extended downtime to address predictable failures.

The isolation extends to consumables. Even filament purchases must be routed through Prusa’s store if users want official material. Shipping Prusament halfway across the world is rarely economical, especially when prices have risen instead of fallen. While competitors offer free or inexpensive delivery over modest thresholds, Prusa expects customers to absorb elevated shipping fees. Loyalty becomes expensive, and for many, irrational.

This narrow structure amplifies every flaw. When a machine has recurring issues, customers cannot simply visit a local distributor. They cannot speak face to face with a technician. They cannot exchange the unit quickly. Instead, they rely on asynchronous conversations with support and hope the problem can be solved remotely. If it cannot, the solution often involves shipping parts or entire machines across borders. These costs are borne by the buyer, not the manufacturer. Resellers offer little relief. Their role is usually limited to order fulfillment rather than service. If a problem occurs, many will simply forward customers to Prusa’s support team instead of handling repairs directly. The reseller becomes an intermediary without responsibility. This structure creates an illusion of international presence while keeping actual support centralized and distant. Buyers gain no practical advantage from these additional storefronts.

The result is a system that punishes anyone outside Europe. Users pay more, wait longer, and receive less. The experience feels at odds with the company’s global reputation. A brand that claims to represent innovation still behaves like a small workshop selling exclusively to nearby customers. Yet its products are marketed to the world. That contradiction undercuts the value proposition for international customers.

Other manufacturers have adopted a different approach. They establish networks that reduce distance between product and support. Local distributors carry spare parts, provide repairs, and simplify logistics. Customers benefit from shorter wait times and lower costs. This infrastructure reflects modern expectations. It demonstrates respect for users’ time and investment. Prusa has not matched this model, leaving its customers isolated by design. Isolation magnifies every weakness. It transforms minor defects into costly failures and routine maintenance into complicated negotiations. It asks buyers to endure uncertainty in exchange for loyalty. In a competitive landscape, such expectations are unreasonable. The barrier is not just technical; it is structural. The company’s refusal to decentralize its operations ensures that distance remains a penalty rather than a simple fact of geography.

Ego as business strategy

Leadership shapes companies, and sometimes it limits them. Josef Prusa built his brand on charisma, openness, and the image of a visionary tinkerer who rose from the maker movement. That personal mythology helped propel his company into the spotlight. But over time, the same personality that once inspired confidence has become a constraint. Decisions appear driven less by market realities and more by the desire to preserve an image. When narrative outweighs engineering, progress stalls. The most telling pattern is how Prusa reacts to competition, instead of setting direction, the company responds defensively whenever others innovate. Bambu Lab introduces a new product, and Prusa announces something soon after. Announcements arrive before prototypes are ready, before details are finalized, and sometimes before the product itself exists. The goal seems less about delivering improvements and more about ensuring that Prusa remains part of the conversation. Presence becomes the objective, not performance.

This reflex reveals a deeper insecurity. Once a leader in consumer 3D printing, Prusa now measures itself through comparison rather than creation. Rather than rethinking legacy design choices, the company appears content to adjust the margins and release iterative updates disguised as breakthroughs. The Core One L is a perfect example: a larger frame marketed as innovation. When scale is presented as progress, imagination has run out. Ego also shows in the company’s unwillingness to acknowledge flaws. Persistent issues with quality control, printed components, and unreliable electronics rarely receive meaningful public explanation. Instead of transparency, the response is often silence or minimization. Customers report failures, and support answers days or weeks later. The culture treats criticism as inconvenience rather than insight. A healthier organization would study these failures to redesign, not defend.

Another sign is the urge to acquire solutions rather than invent them. When Prusa needed multi-material capability, it licensed technology instead of developing its own. When demand shifted toward more advanced toolchanging systems, the company partnered with Bondtech rather than leading. While collaboration can be strategic, reliance becomes dependency when it substitutes for internal innovation. Licensing is not inherently a problem, but when it becomes a pattern, it exposes a creative void.

Even communication reinforces this dynamic. Product reveals are staged events, attended by friendly figures from the community whose proximity suggests endorsement. It blurs the line between genuine enthusiasm and cultivated loyalty. Critics are gently dismissed, while praise receives amplification. The conversation becomes selective. A company confident in its engineering does not need to curate applause; it allows ideas to stand on their merits. The absence of meaningful adaptation shows that preserving the myth matters more than evolving. The origin story of garage-born creativity remains central to the brand’s identity, even though the market now demands more sophisticated execution. This insistence on self-image prevents the company from fully embracing industrial practices that would improve reliability, reduce failure rates, and modernize production. Nostalgia becomes policy. Innovation becomes performance.

Some will argue that personality can drive success. That is true, but only when it adapts. Companies built around individuality must eventually transition to systems that outgrow the founder. Prusa has not made that shift. Decisions still seem tied to one person’s worldview rather than the changing needs of users. This concentration of identity makes criticism feel personal, so it is avoided, and the result is stagnation.

Ego is not always destructive, but here it has become an anchor. A refusal to learn from competitors, to acknowledge internal shortcomings, or to expand distribution because it might dilute control, all point to leadership more concerned with narrative than service. The market keeps evolving. Users keep evolving. When leadership does not evolve with them, the story begins to repeat itself, each chapter less compelling than the last.

Bambu and China run forward

While Prusa circles old ground, others are moving. The companies driving today’s consumer 3D-printing evolution are not spending their time recreating past success. They are building entirely new ecosystems. Nowhere is this clearer than in the rise of Bambu Lab. Instead of iterating on legacy design, they approached the problem from scratch, prioritizing speed, automation, and tight integration between hardware and software. They recognized that most users do not want to maintain their printers. They want to print. Bambu machines demonstrate what happens when engineering leads. Core performance is higher, vibration control is smarter, and motion systems are refined. Calibration is automatic. Filament handling is structured rather than improvised. The machines feel cohesive, as though each subsystem was designed to serve the others. The result is predictable consistency, something Prusa has struggled to deliver across its product line.

Equally disruptive is the ecosystem around these printers. Cameras are standard. Wi-Fi and cloud connectivity are not afterthoughts; they are central features. Firmware, slicer, and mobile app speak the same language. Users can slice a file, monitor a print, and manage machines remotely with minimal friction. These workflows reflect how people actually use technology today. The printer no longer sits alone on a workbench. It participates in a wider digital environment.

Chinese manufacturers beyond Bambu have adopted similar strategies. They focus on reducing the activation barrier for new users. Printers arrive mostly assembled. Instructions are short. Calibration routines run automatically. The tooling and electronics feel modern. The companies assume users want results quickly, and they design accordingly. This assumption has proven correct. The market has responded with enthusiasm. These brands also understand pricing. Their machines cost less while offering more. They leverage economies of scale and efficient supply chains to deliver capable products at accessible prices. This has reshaped expectations. A printer no longer needs to cost over a thousand euros to perform well, proof of this is Snapmaker's announcement of its new multi-toolhead printer for less than 900 euros, which has shaken up the market. Feature sets once reserved for expert machines are available to beginners. The contrast with Prusa, whose prices have risen rather than fallen, is stark.

Innovation is not limited to hardware. Chinese companies are building platforms. Stores, material libraries, cloud spaces, and social features bring users together. These tools help people share, learn, and iterate. They create community through function. Meanwhile, Prusa continues to sell isolated machines with partial infrastructure. The ecosystem that once felt robust now lags behind. Speed of execution reinforces the gap. Competitors develop new models and iterate rapidly. They release revised hardware within months, not years. Firmware updates arrive frequently, responding to real-world user feedback rather than internal timetables. Improvements feel continuous. Owners see their machines grow and mature. Prusa, by contrast, moves slowly, and most changes feel incremental rather than transformative.

This momentum has consequences. New users entering the market encounter Bambu first. They experience automated calibration, high speed, and intuitive interfaces. After that, going backward to slower, manually tuned systems feels unreasonable. The baseline has changed. Once expectations rise, they do not easily fall. A user who begins with Bambu will not accept the compromises that were once standard.

Some traditionalists dismiss this transition as hype. They say users should understand their machines. They say complexity builds character. But technology does not evolve by insisting that people struggle. It evolves by removing friction. The companies leading today understand that. They are not asking users to become mechanics. They are giving them tools that work. That is why their influence grows.

China’s manufacturers are not merely competing. They are defining the future of the segment. They iterate, integrate, and listen. They move from prototype to product quickly. They treat accessibility as a design requirement, not an afterthought. And by doing so, they have expanded the audience for 3D printing beyond hobbyists into classrooms, workshops, and casual studios. They did not wait for permission. They moved.

The maker era is over

A turning point has arrived. For years, 3D printing lived inside a romantic narrative: a world where passionate hobbyists built machines from kits, tuned stepper motors by hand, and celebrated every successful print as a personal victory. The technology was imperfect, but that imperfection felt like participation. Users were collaborators, not customers. Those days shaped the identity of companies like Prusa. They thrived because the culture welcomed experimentation. That culture no longer defines the mainstream. People now approach 3D printers as tools, not projects. They expect them to behave like appliances. The shift is not a betrayal of the past, it is the natural progression of a technology leaving adolescence. When a tool becomes widely useful, it must become predictable. It must disappear behind results; utility overtakes ritual.

This transition exposed a quiet truth: companies that grew out of the maker era must evolve beyond it to survive. Some have. They embraced automation, integration, and modern manufacturing. They reduced friction so that users could focus on design, not diagnosis. They listened to the silent majority who valued reliability over nostalgia. Others resisted, insisting that hands-on difficulty was part of the experience. That insistence now feels out of step with the world around them.

Prusa sits at the crossroads of this transformation. Its identity is built on the values of the past. It once led by democratizing access to open-source hardware, inspiring a generation to explore. But when the market shifted toward speed, cohesion, and simplicity, the company did not pivot. It preserved its heritage instead of expanding its vision. As competitors delivered smoother workflows and stronger ecosystems, Prusa doubled down on handcrafted assembly and incremental upgrades.

Nothing prevented the company from evolving. It had brand loyalty, community support, and name recognition. It could have redesigned its machines from the ground up, built regional support networks, and modernized its supply chain. It could have reimagined the maker spirit rather than freezing it in place. Instead, it allowed confidence to become complacency. Advancement became defense. Innovation became reaction. Customers noticed. They compared the time spent troubleshooting to the time spent creating. They compared shipping expectations, support experiences, and pricing. They weighed the promises against the outcomes. Many who once praised Prusa now look elsewhere. Not because they stopped appreciating the past, but because the future offers more. A tool’s purpose is to enable progress. When it demands too much in return, people move on.

The change is neither sudden nor sentimental. It is practical. Schools want machines that work for students who have never seen a stepper motor. Small businesses want dependable output without maintenance cycles. Designers want to refine concepts, not firmware. This is not laziness. It is clarity. The value lies in the result, not the struggle. The emphasis has shifted from ownership to use. There will always be a place for building machines by hand. Some people enjoy the puzzle itself. They enjoy altering belts, tightening frames, and rewriting profiles. For them, 3D printing remains a craft. But they are no longer the majority. They are a niche within a landscape that has grown broader and more diverse. The mainstream has different priorities, and the companies meeting those priorities will lead.

Prusa helped shape what 3D printing became. That achievement deserves respect. But legacy is not destiny. The story continues with or without those who wrote its opening chapters. The companies that define the next decade will be the ones that respond to new expectations rather than clinging to old victories. The maker era laid the foundation. The next era builds upon it.

Tools must evolve alongside the people who use them. When they do not, they become souvenirs.