Where infrastructure belongs to companies, not citizens

by Kai Ochsen

For most of modern history, citizens relied on governments to provide core services. Roads, utilities, transit systems, and public spaces formed the shared foundation of civic life. They belonged to everyone, funded collectively, and overseen by elected institutions. This arrangement was never perfect, yet it offered a common frame: infrastructure served the public. Today, that assumption no longer holds. Across many regions, private entities have begun to operate and control essential systems once considered the exclusive domain of the state. Electricity grids, water networks, internet access, transport corridors, even security forces increasingly fall under corporate management. These changes arrive quietly. Contracts shift, subsidiaries form, and public agencies step back. The landscape remains familiar, but the ownership beneath it slowly transforms.

This transformation appears most clearly in cities. Urban life now depends on layers of privately managed infrastructure woven through public space. Ride-hail services substitute for public transit. Tech companies provide communication and payment systems. Private broadband providers determine who connects and how fast. Logistics companies determine which neighborhoods receive goods quickly. The city works, but increasingly at the discretion of firms rather than residents. Some of these services feel efficient. Private operators can be faster, more adaptive, or better funded than municipal departments. They innovate where bureaucracy stalls. Yet efficiency comes at a cost: accountability shifts. Citizens lose direct influence over the systems they use every day. They become customers rather than stakeholders. Access depends on terms of service rather than laws. The rules can change without debate.

In this environment, public authority thins. Municipal budgets shrink as governments outsource functions to corporations. Streets may still appear civic, but the code that governs mobility, communication, or public space belongs elsewhere. A resident might walk through a park maintained by the city, but pay for every other service through a private platform. The experience feels seamless, but the power behind it becomes opaque.

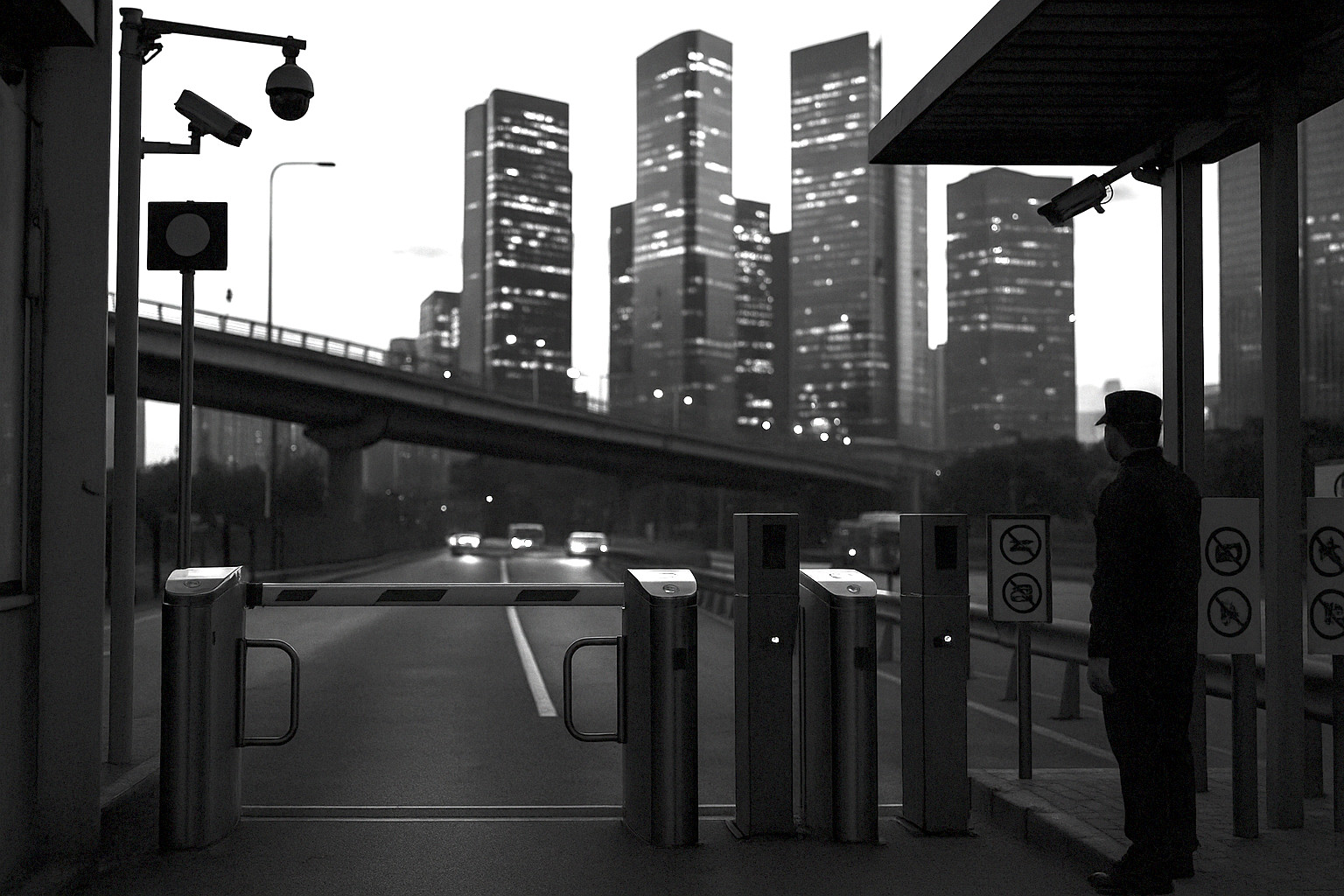

Parallel infrastructures emerge. Some neighborhoods are equipped with high-bandwidth networks, private shuttles, and subscription services. Others receive the minimum, left at the edge of digital participation. The divide is not only economic; it is structural. A city that once offered shared access begins to fragment. Participation depends on purchasing power rather than citizenship. Space becomes tiered, shaped by private priorities. Security follows the same pattern. Private patrols operate in affluent districts. Corporate campuses maintain their own policing. Gated communities separate themselves physically and legally. Even surveillance networks are built and managed by companies, not public institutions. The question of who ensures safety becomes harder to answer. Accountability diffuses into contracts, partnerships, and unexamined agreements.

The underlying shift is cultural as much as economic. People grow accustomed to seeking services from companies rather than governments. They assume that if they pay, systems will function. They assume that private platforms are more reliable than public institutions. The city becomes a marketplace rather than a forum. Its identity shifts from collective to conditional. Shared responsibility dissolves into individual transactions.

What emerges is a new kind of urban order: functional, polished, and increasingly private. It operates through permissions rather than rights, through customer service rather than representation. Citizens continue to live within city limits, but the structures that sustain their lives answer to different authorities. The result is not collapse, but substitution, where infrastructure remains visible, yet no longer belongs to the public it supports.

From public trust to private stewardship

Infrastructure once stood as the physical expression of collective will. Roads, bridges, and power grids carried the imprint of public investment, built through taxation and democratic negotiation. People disagreed about priorities, but they understood that these systems were shared responsibilities. A road did not serve one neighborhood; it served anyone who traveled. The work of maintaining it reflected a social promise.

Over time, fiscal constraints and political pressures pushed governments to seek outside help. Municipalities struggled to fund major projects, particularly those requiring long-term planning and specialized expertise. Corporations filled the gap. At first, they supported public efforts, providing technology or management expertise. Later, they assumed wider roles: designing, operating, and even owning infrastructure outright. Responsibility shifted gradually, contract by contract. This new arrangement grew faster than public understanding. People still saw trains, pipes, and networks as civic property, unaware that private firms increasingly governed their operation. A city might announce a new transit line, but a corporation would manage the revenue. A water utility remained publicly branded, yet profits flowed to external investors. The physical layer still looked public, even when control was not.

Governments welcomed outsourcing because it offered short-term relief. Private financing enabled projects without raising taxes. The burden moved off public budgets, giving officials political cover. But every agreement came with terms: guaranteed profits, exclusive rights, and long concessions. The public gained new services, while corporations gained long-lasting authority. Trade-offs hid inside paperwork few residents ever read. The logic behind privatization emphasized efficiency. Firms claimed they could manage risk better than governments, streamline operations, and deliver faster improvements. In some cases, they succeeded. Yet efficiency created dependence. Once a private operator became indispensable, it could negotiate from strength. Renewals arrived with higher costs. The public could not walk away without destabilizing essential services. The meaning of stewardship changed. Instead of democratic accountability, service quality depended on contractual compliance and shareholder expectations. Complaints traveled through customer service channels rather than civic representation. Residents could not vote out a corporation. Their influence extended only as far as regulatory pressure allowed, and regulators often lacked resources or leverage. Oversight became reactive instead of participatory.

This shift also redistributed expertise. As private firms accumulated operational knowledge, public agencies lost capacity. They became supervisors rather than builders, purchasers rather than designers. Without hands-on skill, governments found it harder to reclaim systems. Dependence deepened. The body that once maintained infrastructure no longer remembered how. Even when public opinion demanded change, practical obstacles stalled it. Examples multiplied. Toll roads transferred to investors for decades. Private utilities determined energy pricing. Telecom companies shaped access to information. The boundaries between public and private blurred. Citizens assumed continuity while the legal structures beneath transformed. Grids and networks remained in place, yet the authority behind them no longer belonged to the community.

Stewardship did not disappear. It changed hands. What was once justified by collective need became governed by commercial logic. Companies did not assume these roles maliciously; they followed incentives. But incentives only loosely matched public priorities. The challenge lies not in their participation, but in their predominance. When stewards answer to shareholders before citizens, the definition of service inevitably changes.

The urban patchwork of private zones

Cities once felt continuous. Streets connected neighborhoods, and public institutions formed a shared skeleton. Anyone could walk through a square, sit in a library, or ride a bus. Today, continuity fractures. Urban environments increasingly consist of fragmented pockets, each governed by different rules. Some blocks feel open. Others operate like subscription services. Access is granted not by citizenship, but by affiliation. Shopping districts provide an early example of this shift. Many now function as privately owned public spaces. They look like open streets, but they are subject to corporate policies. Security guards enforce behavioral standards that differ from municipal codes. Photography may be restricted. Protests may be banned. These areas appear civic but operate under private norms. Public space becomes conditional, shaped by hidden authority.

Corporate campuses extend the logic. Technology companies build vast districts with transportation, security, dining, and recreational facilities available only to employees or approved visitors. These campus zones resemble miniature cities. They are cleaner, safer, and more predictable than their surroundings. Yet they are closed to the broader population. The benefits of urban life concentrate behind access controls. Gated housing communities reinforce the pattern. Developed as solutions to safety or exclusivity, they create boundaries within cities, often with their own governance. Residents pay private associations to maintain streets, parks, and utilities. Rules are set internally, apart from municipal processes. The city exists around them, but the community lives under separate jurisdiction. Authority fragments as pockets of self-management grow. Private transit networks add another layer. Ride-hail services, corporate shuttles, and app-based rentals provide mobility to those who can pay. They bypass public infrastructure, reducing pressure on municipal systems while weakening their political support. Over time, public services stagnate. Those with resources move through seamless private channels. Those without contend with aging networks and limited options.

These pockets do not remain isolated. They interlock into an informal grid. A person can travel from a gated community to a private shuttle, to a corporate campus, to a members-only recreational space, with few interactions in traditional public zones. The city becomes a mosaic of overlapping enclaves, each with its own rules and thresholds. Navigation becomes contingent on membership.

The result is stratification. Physical proximity no longer guarantees shared experience. Neighbors might live side by side yet inhabit different regulatory worlds. One resident accesses premium networks, while another is excluded. The built environment conditions opportunity. It defines which services a person can reach and which communities they can join. Geography fragments into layers of entitlement.

This patchwork weakens traditional civic identity. Cities historically fostered solidarity through shared infrastructure. Public transit, parks, and community institutions brought people together. As these domains shrink, common experience dissolves. People relate more to the private systems they use than to the city they inhabit. Identity shifts from collective to consumer, from citizen to client. The transformation does not erase public space; it reframes it. Some areas remain accessible to all, but they coexist with a growing archipelago of controlled zones. The contrast becomes stark. Streets managed by the city appear underfunded. Spaces managed by companies feel polished. Residents gravitate toward well-maintained enclaves, reinforcing dependence on private provision. The city remains present, but its center of gravity shifts.

Security without the state

Security has long been considered a core function of government. Police, courts, and public patrols embodied the state’s promise to protect its people. That promise has weakened. Across many cities, private actors now perform much of the work once reserved for official institutions. They patrol streets, monitor neighborhoods, and enforce their own standards. Public authority persists, but often at the margins. Private security firms have become a fixture of urban life. Their uniforms resemble those of public police, but their obligations differ. They answer to clients rather than communities. Contracts define their priorities. These agents guard malls, campuses, housing developments, and transit hubs. Their presence is visible, yet their accountability is limited. Protection follows payment, not citizenship.

Corporate policing expands this model. Large companies run internal security forces equipped with advanced surveillance, proprietary intelligence, and physical response units. Some coordinate closely with local authorities; others operate independently. These forces focus on safeguarding assets, data, and employees. They maintain order within defined boundaries. Outside those boundaries, responsibility transfers back to public agencies, often unevenly. Gated communities rely heavily on private patrols. Residents pay fees for controlled access, rapid response, and tailored enforcement. The security presence feels immediate and personal. It can also be selective. Patrols may respond quickly inside the gates and ignore concerns just outside them. The boundary becomes more than a fence; it becomes a line between two systems of protection.

Technology deepens this division. Home surveillance networks, automated alarms, and neighborhood apps allow residents to monitor surroundings and share information instantly. These tools increase perception of safety, but shift responsibility from public institutions to private platforms. Decisions about data, access, and enforcement remain opaque. People rely on companies to filter risk, often without considering the trade-offs.

Public policing evolves around these changes. Officers may formalize partnerships with private entities, using shared intelligence or co-patrol models. These arrangements can improve efficiency, but blur accountability. When an incident occurs, responsibility becomes diffuse. Was it a matter for the city, the corporation, or the contractor? Lines of authority overlap. Citizens struggle to understand who answers to whom. The imbalance affects who receives attention. Commercial districts with private support enjoy continuous monitoring. Residential areas without such resources wait longer for public response. The map of safety aligns with wealth. Access to protection becomes a consumer good rather than a civic guarantee. Those outside private networks depend on overstretched agencies with fewer tools and slower response times.

Legal boundaries complicate the picture. Private security can intervene quickly but must operate within limited authority. They may monitor, question, or detain, but rely on public police for arrest. This interplay creates tension. In some cases, private actors exceed their mandate, enforcing rules without legal standing. In others, they retreat, leaving gaps in protection. Clarity gives way to improvisation. As these systems expand, the meaning of public safety evolves. People begin to view protection as a service rather than a right. They evaluate providers like vendors. Satisfaction depends on speed and convenience. The idea of a common security framework weakens. Safety becomes stratified, a function of access rather than belonging. The state remains present, but its role shifts from primary guardian to secondary participant.

Utilities behind paywalls

Electricity, water, and communications once functioned as universal guarantees. These networks were understood as foundational, like roads or schooling. Access was broad and protected by public oversight. Over recent decades, that framework has eroded. Utilities increasingly operate as commercial products, where access depends on contracts, credit, and geographic luck rather than a shared civic promise. Electricity illustrates this shift clearly. In many regions, power generation and distribution belong to private corporations. They decide pricing, maintenance schedules, and investment priorities. Regulatory bodies exist, but often struggle to enforce standards. Market logic dominates, especially in places where competition is weak. Households sign contracts like they would for a streaming service. Their rights feel transactional, not fundamental.

Water utilities follow a similar path. When municipal systems encounter financing shortfalls, governments turn to private operators. These firms promise upgrades, but cost often rises. Residents pay for reliability through tiered pricing structures. Those who fall behind risk disconnection. The notion of water as a universal right becomes tenuous when supply depends on billing cycles and shareholder expectations.

Telecommunications demonstrate how privatized infrastructure shapes daily life. Internet access has become essential for education, employment, and public services. Yet broadband deployment depends heavily on corporate interest. Some neighborhoods enjoy high-speed fiber, while others wait years for basic coverage. The digital divide reflects corporate priorities more than public need. Being connected depends on whether a provider sees profit, not on whether a community requires access.

Subscription models reinforce these divides. Utilities bundle services into layered plans, offering speed, reliability, or priority response at different price points. Residents with resources enjoy stable networks and rapid resolution of outages. Others accept slower speeds or extended delays. Infrastructure stratifies experience. Utility access begins to resemble membership tiers rather than public guarantees. The rise of metering deepens the trend. Smart devices track usage in real time, allowing companies to tailor billing and control distribution. These tools promise efficiency, yet introduce new vulnerabilities. Users accept remote shutoffs or throttling controlled by corporate systems. In some regions, energy providers reduce supply during peak hours. The grid becomes responsive, but users lose agency. Decisions happen far from public scrutiny.

Alternative providers complicate the ecosystem. Solar companies, water recapture firms, and private internet services offer autonomy for those who can afford installation. Households capable of paying upfront gain partial independence, while others remain tied to aging networks. This divergence accelerates inequality. Infrastructure becomes a personal asset rather than a shared foundation.

Public oversight struggles to keep pace. Regulatory commissions balance affordability, reliability, and corporate viability. When disputes arise, hearings replace democratic negotiation. Residents must navigate legal frameworks to contest pricing or service failures. These processes are slow and technical. Few have the time or expertise to engage. Accountability drifts toward specialized channels, far from the public square.

The transformation of essential services into purchasable products alters daily life in quiet but lasting ways. Households learn to navigate providers as they would any marketplace, comparing prices, incentives, and penalties. Reliability depends less on collective guarantees and more on individual arrangements. Over time, people adjust to the idea that even the most fundamental systems require negotiation and vigilance. What was once shared becomes segmented, leaving access shaped more by circumstance than by common obligation.

Mobility through membership

Movement once depended on public systems. Buses, trains, and municipal roads formed the backbone of transportation. They provided broad access regardless of income. If the network struggled, the public debated solutions. Investment cycles followed political decisions. Today, that structure has diversified. Private platforms now sit alongside traditional transit, offering convenience to those who can pay. Ride-hail companies mark the clearest departure. Their services operate on demand, routing passengers through algorithms rather than scheduled lines. Prices fluctuate with time and location. Riders accept the terms because the experience feels seamless. Yet availability concentrates in profitable areas. Dense corridors receive continuous coverage, while low-income districts wait longer or pay more. Convenience follows demand, not equality.

Corporate shuttles extend this pattern. Large employers maintain dedicated networks that move thousands of workers daily. These systems relieve pressure on public transit but reinforce separation. Riders travel in controlled environments inaccessible to others. Cities benefit from reduced congestion, yet become dependent on private fleets. Routes align with corporate priorities rather than civic planning. Micromobility services add another layer. Electric scooters and bikes populate sidewalks, accessed through apps and subscription plans. They offer flexibility, yet invite fragmentation. Some neighborhoods feature dense clusters of devices. Others have none. The physical presence of these fleets reflects commercial logic, not community need. The map of movement becomes irregular, shaped by profitability.

Payment structures create subtle barriers. Transit passes once provided universal access. Now, multiple platforms require separate accounts, deposits, and verification steps. Navigating the city demands a portfolio of memberships. The friction increases for visitors or residents without stable banking. Mobility becomes tied to digital identity as much as geography. The ability to move reflects administrative status, not just location. Integration between systems remains limited. Public and private services coexist, but rarely coordinate. A person may take a city bus, then rely on a ride-hail app to finish a journey, but timetables and pricing remain disconnected. Transfers become complex. This disjointed landscape encourages users to choose the most convenient private option, further weakening public networks.

Inequality appears not only in access, but experience. Riders with subscriptions enjoy priority support, faster routes, or cleaner vehicles. Those who depend on public transport confront aging infrastructure and longer delays. The narrative shifts. Public systems come to be seen as backups, not infrastructure. Confidence erodes, reinforcing a cycle of underinvestment and decline.

Governments attempt to regulate these platforms, but leverage is limited. Private mobility companies negotiate from strength, citing their importance to urban flow. When tensions escalate, they may threaten withdrawal, leaving cities scrambling. The relationship becomes transactional. Municipalities compromise to maintain service, even when it conflicts with long-term planning. As mobility becomes modular and conditional, the meaning of public movement changes. People may travel farther and faster, but not equally. The city remains navigable, yet access feels contingent. The road no longer belongs to everyone, but to whoever can participate in the system that governs it. The promise of shared movement quietly recedes.

Data as a new jurisdiction

Information now flows through private arteries. Every ride taken, payment made, door unlocked, or shipment delivered leaves a digital trace. These traces accumulate in systems managed not by governments, but by corporations. They form maps of human behavior, revealing patterns more detailed than any census. The institutions that collect this knowledge gain influence beyond infrastructure. They operate as unseen jurisdictions. Data replaces proximity. A company that processes transactions for an entire region knows more about its population’s habits than many local authorities. It can identify when neighborhoods rise or decline, when demand swells, or when shortages loom. Insight becomes leverage, guiding decisions about investment and service expansion. Municipalities face their own cities interpreted through corporate analytics.

Consent emerges as a fragile concept. People rarely understand how their data is used. Terms of service grant broad permissions, allowing companies to store, analyze, and share information. These agreements are not negotiated; they are accepted as conditions of participation. Opting out often means losing access. The choice feels symbolic rather than real. This arrangement creates new forms of governance. Instead of laws, platforms enforce rules through code. A suspended account becomes a kind of exile. A flagged address may receive slower delivery or limited support. The penalties are quiet but significant. They shape daily life without public debate. Accountability rests on customer service rather than representation.

Governments increasingly rely on private data. Public agencies license access to corporate platforms, seeking insights they cannot generate alone. Health departments analyze mobility data from telecom firms. Transportation agencies review routing information from ride-hail services. Policymaking becomes dependent on datasets they do not own. Influence shifts to those who control information rather than those who hold office. Security concerns amplify the shift. Data centers operate with minimal public visibility. Their servers store crucial information about households, businesses, and institutions. Outages or breaches can cripple essential functions. Yet local officials may have limited authority to intervene. Responsibility falls on internal protocols and contracted cybersecurity firms. The protection of sensitive information becomes privatized.

Jurisdictional complexity deepens across borders. A city may govern physically, but the data generated within it travels globally. Corporations store records wherever it suits their infrastructure. Local laws struggle to constrain actors who operate across continents. Enforcement becomes elusive. Public authority loses ground in a landscape defined by international corporate networks. Some regions attempt to reclaim control through regulation. They mandate data localization, transparency, or consent requirements. Yet these measures face resistance. Companies warn of higher costs or reduced innovation. Negotiations become prolonged, technical, and uneven. Even when rules are enacted, enforcement remains uncertain. Regulation trails technology by years.

As data becomes a form of territory, the line between public and private authority blurs. Cities rely on systems they do not own, while residents live inside digital frameworks they cannot influence. The new jurisdiction is silent, embedded in code and contracts. People continue their routines, unaware that the boundaries of power have shifted beneath them.

Citizens without a city

Citizenship once implied a reciprocal bond. People contributed to public life, and in return benefited from shared institutions. Schools, transit, and utilities expressed this mutual commitment. Today, that bond feels thinner. As infrastructure shifts into private hands, the idea of belonging to a city through rights and responsibilities begins to erode. The role of the citizen weakens, leaving individuals adrift inside systems that regard them mainly as users. Participation follows new pathways. Instead of voting for better transit, residents subscribe to mobility platforms. Instead of petitioning for improved broadband, they negotiate with providers. These choices occur at the individual level, without collective expression. People solve their own problems rather than pursue common solutions. The political dimension of infrastructure gradually disappears from public life.

The consequences extend beyond convenience. When essential systems operate as services, residents no longer shape them through democratic means. They cannot demand equitable access or long-term investment. Instead, they weigh the cost of switching providers. Politics turns private. Decisions that once emerged from councils and assemblies now emerge from boardrooms. Voice becomes limited, reduced to customer feedback forms. This realignment affects identity. Belonging to a city meant sharing its burdens and benefits. Municipal pride grew from common institutions. As those institutions fade, pride becomes more aesthetic than civic. People appreciate the skyline, a park, or a cultural scene, while the underlying mechanisms function independently of public will. The sense of collective ownership diminishes.

Social ties also weaken. Public infrastructure once forced encounters among strangers. Buses mixed professions and classes. Libraries hosted shared learning. Utilities reached into every home. Private networks filter interactions. Membership cards and digital keys decide who crosses which thresholds. People travel in parallel rather than together. Encounters become patterned by access, not place.

The financial model reinforces separation. Cities depend less on taxation and more on partnerships, concessions, and external investment. Residents pay indirectly through service fees rather than public levies. This shift obscures responsibility. When systems fail, blame circulates. The city points to contractors, and contractors point to regulators. Citizens find no stable point of accountability. For many, the experience feels manageable. Services work, deliveries arrive, and apps keep life organized. Yet beneath the surface lies vulnerability. When private systems change policy or suspend service, individuals have few protections. There is no constitutional right to a subscription. There is only continued eligibility. Access depends on good standing and compliance, not civic status.

Younger generations adapt to this landscape without reference to an earlier model. They grow up with the assumption that essential services are purchased individually rather than guaranteed collectively. Their expectations reflect the world they inherit. Citizenship becomes less about shared governance and more about strategic navigation. The city feels less like a house and more like a network. The result is a quiet estrangement. Residents occupy the same territory but no longer inhabit a shared civic story. They move through zones rather than communities, experiencing the city as a series of transactions. The rituals of belonging fade, replaced by seamless interfaces and personalized solutions. What remains resembles citizenship in name but not in spirit, leaving people unsure where participation begins or whether it matters at all.

A future divided by infrastructure

The long-term consequences of privatized civic systems remain unclear, yet early signs suggest widening separation. Some communities move fluidly through their environments, supported by premium networks and responsive services. Others navigate broken roads, unreliable connections, and higher costs. This divergence reflects not only economic inequality, but structural differences baked into the design of modern life. The gap becomes physical as well as conceptual. Private infrastructure fosters new forms of concentration. Wealthy districts invest in advanced connectivity, dedicated transit, micro-grids, and closed security networks. Their residents experience reliability as default. Power outages are rare, deliveries arrive instantly, and support is always available. These neighborhoods operate as functional islands, plugged into global networks yet insulated from local decline. They resemble independent micro-states.

Meanwhile, regions without corporate interest fall behind. Public networks age without adequate funding, and service providers hesitate to invest without guaranteed returns. Households rely on outdated infrastructure that struggles under modern demands. Repairs come slowly. Transit routes narrow, water systems falter, and broadband remains limited. Residents learn to adapt, but adaptation often means diminished opportunity. Geography reinforces inequity.

Migration patterns respond. People who can afford it relocate toward well-managed private zones, leaving weaker public areas further depleted. This movement accelerates fiscal imbalance. Municipalities serving fewer high-income residents suffer declining tax revenue while still maintaining broad infrastructure. The remaining population carries disproportionate burden. Buildings decay, businesses close, and communities hollow out. Decline becomes self-reinforcing. Political influence reflects these shifts. Residents in private zones rely less on government services, reducing incentive to support public investment. Their engagement with civic structures weakens. Decisions affecting the wider city matter less because their daily lives depend mainly on private providers. Public institutions lose relevance among those with the most resources. Policy becomes guided by narrower interests.

Innovation deepens the divide. Technologies such as autonomous vehicles, advanced grids, and private emergency systems will likely debut in privileged networks. These systems test, refine, and expand where profits are guaranteed. Only later, if ever, do they reach broader populations. The benefits that once spread outward through public investment now circulate within controlled environments. Progress becomes gated.

Some propose hybrid solutions. Companies partner with governments to extend upgraded services to under-resourced areas. These arrangements produce short runs of improvement, yet often leave ownership and decision-making firmly in private hands. When partnerships dissolve, support can vanish. Plus, public agencies remain responsible for maintenance, even when they lack the funds or expertise to sustain the systems they inherited.

Social cohesion dissipates in this landscape. People live in the same metropolitan region yet rarely share institutions, spaces, or experiences. Trust erodes when public systems appear incompetent while private ones appear untouchable. Inequality feels permanent, anchored to infrastructure rather than culture. The promise that cities unify diverse populations weakens as shared foundations disappear. The trajectory is not irreversible. Some cities experiment with reclaiming public control over key services, building municipal broadband, electrifying transit, or reestablishing shared utilities. Their efforts demonstrate that alternatives remain possible, though costly and slow. They also reveal a central truth: infrastructure is destiny. Whoever controls it shapes not only mobility, communication, and safety, but the meaning of community itself.

What cities become when ownership shifts

Urban life does not change all at once. It evolves through adjustments that seem modest at first: a private contractor managing utilities, a housing developer adding security staff, a technology company offering transportation options. Each step feels practical. The motivations appear reasonable. What is harder to see is how these choices accumulate. They redraw the boundaries of belonging. For generations, cities represented a shared project. People contributed through taxes, service, and participation, and received access to infrastructure in return. The streets, libraries, and water systems were imperfect, yet they offered a baseline of common provision. That baseline now wavers. Services that once defined civic identity increasingly answer to private logic. Residents become customers whose rights fluctuate with market interest.

Every shift alters expectations. When electricity becomes a contractual privilege rather than a guaranteed service, people accept interruptions as terms rather than failures. When transit depends on subscriptions, riders internalize the need to qualify. Over time, citizens learn to navigate environments shaped not by collective purpose but by variable access. The city becomes conditional, its structure guided by the logic of membership rather than community.

These dynamics do not automatically produce decline. Private networks can be efficient, responsive, and innovative. They allow rapid deployment of technology that governments struggle to fund and manage. But their success raises questions that efficiency cannot answer. Who participates in decisions? Who is excluded? Who benefits when systems function well, and who bears the cost when they fail?

The greatest risk is not fragmentation alone, but normalization. People begin to assume that segmented systems are natural. Gated streets, paywalled services, and selective transit feel standard. Public institutions appear slow by comparison, and thus unnecessary. A generation grows up believing that rights are indistinguishable from subscriptions. The language of citizenship gives way to the language of access. In this environment, accountability dissipates. Failures lead to finger-pointing between agencies and contractors. Residents struggle to identify who is responsible. The mechanisms of democracy, once tied to daily experience, lose relevance. Voting carries less weight when essential services fall outside political influence. The gap between policy and lived reality widens, leaving representation without a foundation.

Still, responses exist. Some regions pursue municipal broadband, shared transit investments, or open-access utilities. Others explore public oversight of private networks. These efforts acknowledge that infrastructure shapes more than convenience; it shapes identity. They suggest that collective control can coexist with innovation, and that public interest remains a legitimate organizing force. Whether such alternatives spread depends on cultural instinct as much as policy. If citizens believe shared systems matter, they will defend them. If they accept that everything is transactional, private networks will continue to prevail. The direction is not determined by technology, but by what people choose to value: convenience alone, or belonging that extends beyond individual benefit. The future city will not be purely public or purely private. It will reflect the balance societies strike between efficiency and solidarity. Some will embrace segmented models that reward purchasing power. Others will rebuild institutions that serve residents as participants rather than clients. The question is not which model wins, but what kind of civic life emerges when infrastructure no longer defines a common world.

What remains is a reminder: cities grow from decisions about who is included and who is not. Ownership shapes those decisions. When the foundations of daily life belong to companies rather than communities, the meaning of living together changes. The challenge is recognizing that shift while something can still be done about it.