The last samurai of modernity: Yukio Mishima and the value of conviction

by Kai Ochsen

In this post, I want to reflect on a figure who remains surprisingly little known in the West, a man whose story is both fascinating and tragic, but also profoundly worth remembering, because few figures of the twentieth century embody the tension between modern decadence and ancient honor as vividly as Yukio Mishima. To some, he was one of Japan’s greatest novelists, a man whose prose dissected the beauty and cruelty of existence with unmatched elegance. To others, he was a reactionary eccentric, obsessed with outdated ideals of tradition, discipline, and sacrifice. But whatever one’s interpretation, there is no denying that Mishima was a man of uncompromising conviction. He was a writer who lived not only through words but through action, a man who believed so strongly in his philosophy that he was willing to die for it, and did.

Today, Mishima’s name is often whispered with controversy or entirely forgotten, overshadowed by a culture that no longer tolerates uncomfortable questions about meaning, duty, and conviction. And yet, his story matters now more than ever. At a time when society celebrates comfort over discipline, pleasure over sacrifice, and conformity over critical thought, revisiting the life and work of Yukio Mishima is to confront a challenge: what does it mean to hold fast to principles so tightly that you are prepared to give your life for them?

Mishima’s life was not merely a literary journey; it was a carefully constructed performance, an attempt to fuse art and action, body and spirit, into a singular, unbroken statement. His death, ritual suicide by seppuku in 1970, staged after a failed attempt to rally Japan’s Self-Defense Forces in a coup, was not an act of madness, but the culmination of his philosophy. He believed that words without deeds were hollow, and that the modern world had lost touch with the honor that once defined civilizations. His final act was at once shocking and coherent, the inevitable climax of a life dedicated to conviction.

In reflecting on Mishima, we must resist both the temptation to romanticize him blindly and the dismissive ease of labeling him a fanatic. Instead, we can approach his story as an uncomfortable mirror. He exposes the poverty of our own time, an era in which beliefs are shallow, principles negotiable, and sacrifice avoided at all costs. He reminds us that the value of conviction lies not in whether we agree with a man’s ideals, but in the fact that he dared to live and die by them, in stark defiance of the relativism and apathy that dominate our age.

The writer and the aesthete

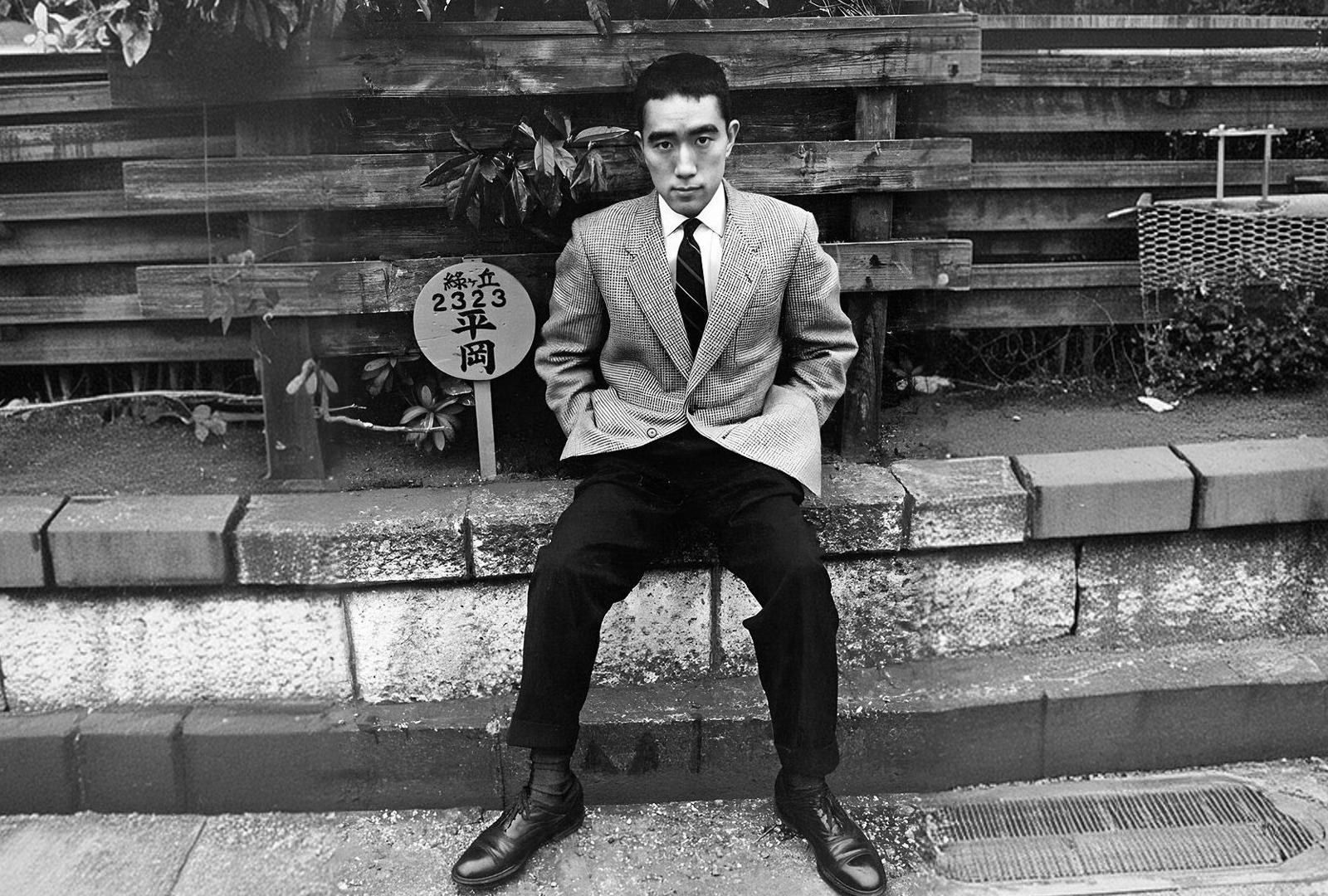

Yukio Mishima was, first and foremost, a man of letters. Born in 1925 as Kimitake Hiraoka, he adopted the pen name Yukio Mishima as a shield, both to protect his family from scandal and to craft the myth of himself as an artist. From a young age, he displayed extraordinary talent, producing stories of haunting beauty and morbidity, themes that would define his career. His early works already revealed his obsession with the interplay of life and death, desire and destruction, and the pursuit of aesthetic perfection.

Over the course of his career, Mishima wrote more than thirty novels, alongside plays, essays, and short stories. His most famous works, Confessions of a Mask, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, and the four-volume epic The Sea of Fertility, remain landmarks of Japanese literature. In them, he explored themes of identity, obsession, sexuality, and nihilism, always with prose that balanced clarity with lyricism. His characters often struggled with the same dilemmas that consumed Mishima himself: the tension between the spiritual and the carnal, between tradition and modernity, between the desire to live and the allure of death.

But Mishima was not content to remain a creature of the page. He believed in the unity of word and action, and he feared that literature alone was too fragile, too ephemeral to embody the truths he sought. He cultivated his body with the same intensity he applied to his prose, taking up bodybuilding, martial arts, and kendo. His transformation from a sickly youth into a muscular, disciplined adult was more than vanity; it was a statement. For Mishima, the body was a canvas, a way of living out the ideals of strength, beauty, and mortality that he wrote about. To separate his art from his life would be hypocrisy.

This obsession with the aesthetic extended to how he lived his daily existence. Mishima treated his life as a work of art in itself, an ongoing performance. He posed for photographs, not just as a writer, but as a warrior, a martyr, a man out of time. He understood the power of imagery in the modern world, and he harnessed it, sculpting himself as much as his sentences. He believed that to live beautifully was to die beautifully, and that every aspect of one’s life should be shaped in accordance with that pursuit.

Through his art, Mishima confronted the void of modern existence. He saw a Japan that had surrendered its spirit in the aftermath of World War II, embracing material comfort and Western consumerism at the cost of its cultural essence. His novels reflected this disillusionment, portraying characters adrift in a world stripped of meaning, their desires consuming them in the absence of higher ideals. For Mishima, literature was a way to diagnose the sickness of his time, but it was not enough to cure it.

In Mishima’s view, true art demanded not only the creation of words, but the embodiment of them. To write about honor without living honorably was cowardice; to romanticize death without confronting mortality was hypocrisy. This conviction would ultimately carry him beyond the role of novelist, into the realm of political activist, soldier, and martyr. His writings gave him a voice, but his actions, however extreme, gave him coherence. He would not merely write of death and sacrifice; he would live them.

The man of conviction

The turning point in Yukio Mishima’s life came when he decided that words alone could not sustain his philosophy. He had already achieved literary fame, wealth, and international recognition, but he felt an inner emptiness in the applause. For Mishima, literature was only half of the equation; the other half was action, the embodiment of ideals in the physical and political realm. To speak of honor without living it was, in his eyes, hypocrisy. To glorify death without embracing it was cowardice. His destiny, as he saw it, was not just to write beautifully, but to live and die beautifully.

In postwar Japan, Mishima found fertile ground for his discontent. The country, devastated by World War II and shaped by American occupation, had reinvented itself as a pacifist, consumerist society. For many Japanese, this transformation meant relief, stability, and prosperity after years of suffering. For Mishima, however, it represented a spiritual defeat. He believed Japan had lost its soul, its traditions, its sense of honor, its willingness to sacrifice for something greater than material comfort. The ancient ideals of the samurai, embodied in bushidō, had been abandoned, replaced by neon lights, corporate hierarchies, and shallow pleasures.

Mishima could not accept this trajectory. He began to move beyond literature, writing essays and speeches that attacked what he saw as the decadence of modern Japan. He denounced the obsession with money, the blind embrace of Westernization, and the loss of martial spirit. More than mere criticism, his words were a call to arms: a plea to restore Japan’s traditional values and to revive the honor that had been buried under the rubble of defeat. His voice was sharp, provocative, and unafraid to confront the apathy of his time.

But Mishima was not satisfied with words alone. In 1968, he founded the Tatenokai, or Shield Society, a private militia of young students devoted to traditional ideals and trained in the way of the warrior. On the surface, it may have seemed theatrical, a novelist playing soldier. Yet for Mishima, the Tatenokai was deadly serious. He trained his men rigorously, instilling in them not just martial skills but also a philosophy of honor, loyalty, and sacrifice. He wanted to prove that in an era of consumerism and pacifism, there were still those willing to live, and die, for conviction.

The creation of the Tatenokai was more than a personal project; it was a direct challenge to Japan’s new order. By organizing a paramilitary group, Mishima was implicitly questioning the legitimacy of a society that had renounced the warrior spirit. He was also preparing the stage for his own final act. In his mind, the Shield Society was not just about defending tradition; it was about demonstrating that conviction without compromise still existed. He believed that his generation had been castrated by comfort, lulled into passivity by economic growth. Through his small band of followers, Mishima sought to reignite the flame of discipline and sacrifice.

What set Mishima apart from mere radicals or political agitators was the depth of his aesthetic and philosophical consistency. He was not a man who acted out of opportunism or vanity. Everything he did, from bodybuilding to kendo practice, from writing to political activism, was part of a singular vision: the unity of body, spirit, and action. He was convinced that true greatness required alignment between word and deed, and he sought to embody that alignment in every aspect of his life.

For Mishima, Japan’s embrace of pacifism was not only a betrayal of tradition but also a denial of life’s deepest truths. He believed that death gives life its meaning, that the possibility of sacrifice is what elevates existence above mere survival. A society that refuses to die for its values, in his view, is a society that has already surrendered. These were not abstract ideas for Mishima; they were the principles by which he measured his own worth. To live without conviction was to live in dishonor.

This philosophy placed him on a collision course with his era. While most of his contemporaries embraced prosperity and peace, Mishima declared that he would rather face ridicule and isolation than surrender his principles. He wrote, he trained, he spoke, but above all, he lived in defiance of the complacency he saw around him. His conviction made him both a relic of the past and a prophet warning of the future. And as his discontent with words deepened, it became increasingly clear that Mishima’s story could not end in ordinary life. For a man who sought coherence between literature and existence, between philosophy and action, the stage was being set for the dramatic conclusion that would shock the world.

The final act

By the late 1960s, Yukio Mishima had reached a point of no return. He had written his masterpieces, achieved international fame, and even secured a Nobel Prize nomination. But he was restless, convinced that words alone were no longer enough. His philosophy demanded coherence between life and death, and for Mishima, that coherence required an act that would fuse his art, his politics, and his body into a single, unforgettable statement. What he envisioned was not merely a protest, nor even a gesture of defiance, but a performance on the stage of history, a final act that would give ultimate meaning to his convictions.

On November 25, 1970, Mishima carried out what he had long prepared for. Accompanied by four members of his Tatenokai militia, he entered the headquarters of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces in Tokyo under the pretense of visiting a general. Once inside, they barricaded the office and tied up the officer, then Mishima stepped out onto the balcony to address the assembled soldiers below. His words were not improvisation; they were the culmination of years of writing and living. He called upon the soldiers to rise up, to restore the Emperor’s powers, and to reject the spiritual emptiness of postwar democracy. He denounced the pacifist constitution as a betrayal of Japan’s essence, a castration of its warrior spirit.

The soldiers, however, did not respond with enthusiasm. They mocked him, jeered at him, some even laughed. Mishima’s impassioned speech fell flat, a reminder that his ideals were deeply out of step with the times. For him, though, the reaction hardly mattered. He had not staged this coup to win power, but to create a moment where his philosophy would be fully enacted. If words failed, action would speak louder.

Returning to the office, Mishima began the ritual he had long promised: seppuku, the samurai’s act of self-disembowelment. For him, this was not madness, but the fulfillment of his belief that death was the ultimate aesthetic gesture, the only way to preserve honor and coherence between word and deed. In his writings, he had declared that a life devoted to beauty must also end beautifully, and for Mishima, beauty meant sacrifice, discipline, and control over one’s fate. To live endlessly in compromise was a fate worse than death; to die in full possession of one’s convictions was victory.

The act was gruesome, and in modern eyes almost incomprehensible. But to Mishima, it was the logical culmination of his life. His death was not an escape from failure, but the proof that his philosophy was more than rhetoric. By taking his own life in ritual fashion, he claimed the authority of the samurai, aligning himself with Japan’s martial traditions and rejecting the softness of modernity. The brutality of the act was, for him, the source of its meaning. It was a declaration that conviction mattered more than survival, and that honor demanded sacrifice.

The world’s reaction was one of shock and confusion. International media portrayed him as a madman, a reactionary eccentric, or a deluded extremist. In Japan, his death was received with discomfort, many dismissing him as an anachronism clinging to a past that no longer existed. But there were also those who recognized in his final act a kind of terrible consistency, a refusal to live at odds with his ideals. Even those who disagreed with his politics could not ignore the coherence of his life and death. He had become what he had always sought to be: a man whose existence was indivisible from his art, a writer who had written his final masterpiece not on paper but in blood.

For Mishima, the coup attempt and ritual suicide were not failures but fulfillment. He never truly believed that his words would incite a revolution; he believed instead that his death would serve as a statement louder than any novel or speech. In this sense, November 25, 1970, was not an end but a culmination, the closing act of a performance he had crafted throughout his life. He had lived as a writer, a soldier, an aesthete, and a prophet of conviction. He died as all of these combined, proving to himself, and to history, that he was a man who refused compromise.

It is difficult for us, in an age that avoids discomfort at all costs, to fully grasp the meaning of Mishima’s final act. But what cannot be denied is that his death remains one of the most shocking and symbolic gestures of the modern era. It was a reminder that conviction can still exist in its purest, most uncompromising form, even if the world no longer has ears to hear it. Mishima’s seppuku was both a tragedy and a triumph: a tragedy because it ended the life of a brilliant artist, and a triumph because it gave him the unity of word and action he sought above all else.

Mishima’s philosophy

To understand Yukio Mishima is to look beyond the spectacle of his death and to see the philosophy that shaped his life. His works, his public persona, his physical transformation, his politics, and ultimately his ritual suicide were not disparate events but fragments of a unified vision. Mishima believed in the inseparability of beauty, honor, and death, and he sought to live in such a way that these elements converged into a single statement of meaning. His philosophy may unsettle, but it remains a rare example of consistency between belief and action.

At the center of Mishima’s worldview was the conviction that words without deeds are empty. As a novelist, he had mastered the art of language, but he grew increasingly dissatisfied with the idea that writing alone could convey the truth he pursued. For him, literature that glorified sacrifice while the author lived comfortably was hypocrisy. He saw in modern society, both in Japan and the wider world, a widening gulf between what people said and what they did. Politics, art, and daily life were filled with declarations of principle, but few were willing to pay the price of living by them. Mishima rejected this dissonance. He insisted that aesthetics and ethics, thought and action, body and spirit must be one.

This belief shaped his obsession with the body as an extension of the soul. He transformed himself from a fragile, sickly child into a sculpted man of discipline through bodybuilding, kendo, and martial training. To Mishima, the body was not vanity; it was a sacred vessel, a way of embodying ideals physically. Just as he honed his prose to perfection, he honed his body to mirror his philosophy of strength, beauty, and mortality. The body, he argued, should be an instrument of conviction, not a passive shell. His physical discipline was not separate from his art but a continuation of it.

Another pillar of Mishima’s philosophy was his reverence for tradition and honor, rooted in Japan’s samurai heritage. He believed that postwar Japan had lost touch with its essence by embracing material prosperity at the expense of its spirit. In his view, a society that seeks only comfort and safety becomes spiritually bankrupt. For Mishima, honor was not an archaic relic but the foundation of meaning in life. Without the willingness to sacrifice, without the recognition that death gives life its value, existence becomes shallow, guided only by consumption and survival. This is why he considered death not as an end but as the ultimate aesthetic gesture, a way of giving life coherence.

Mishima also saw beauty as inseparable from mortality. In his essays, he wrote often about the fleeting nature of flowers, the impermanence of youth, and the tragedy of decay. To him, beauty was precious precisely because it was transient. Death was the moment that crystallized beauty, preserving it from corruption. This aesthetic sensibility ran through his novels, where characters often destroyed what they loved in order to preserve its perfection. His own death followed this logic: by ending his life in ritual sacrifice, he sought to capture the essence of his philosophy in one final, uncorrupted gesture.

At the same time, Mishima was acutely aware that he was out of step with his age. The world around him embraced relativism and comfort, while he preached absolutes and sacrifice. He was not naive; he knew his ideals would not be embraced by the masses. But he believed that a life without conviction was worse than death, and so he chose to live as an anachronism, a relic of a time when honor mattered more than profit, when sacrifice was seen as noble rather than absurd. His philosophy was not pragmatic, but it was coherent, and coherence was for him the highest virtue.

What makes Mishima’s philosophy so arresting is not that we must agree with it, indeed, many will find it extreme, even dangerous, but that it exposes the poverty of our own time. We live in an era where principles bend to convenience, where words are cheap and easily forgotten, where comfort is valued above all. Mishima reminds us, uncomfortably, that conviction has a cost, and that without sacrifice, principles are nothing more than slogans. His life, however extreme, forces us to confront the question: how much do we truly believe in the values we claim to hold?

In the end, Mishima’s philosophy can be summed up in his insistence on the unity of thought and action. He believed that a person should live in such a way that their existence was indivisible from their beliefs. For him, art, body, tradition, and sacrifice were all threads in a single tapestry. He rejected compromise not because he failed to see its appeal, but because he considered it dishonorable. He died not because he despaired, but because he believed that only through death could he affirm the life he had lived. Whether we admire or condemn him, Mishima stands as one of the rare figures in modern history who refused to betray his convictions.

Contrast with today

To measure the life and philosophy of Yukio Mishima against the backdrop of today’s world is to recognize a chasm between conviction and complacency, between a man who lived and died for principles and a society that increasingly avoids principles altogether. Mishima’s ideals, discipline, honor, sacrifice, and the unity of word and action, now seem like artifacts from another age, drowned beneath the noise of consumerism and the cult of comfort. His story reminds us of what has been lost: not simply a vision of Japan rooted in tradition, but a universal belief in the necessity of conviction as the foundation of a meaningful life.

We live in an era where values are endlessly negotiable. Principles bend under the slightest pressure of convenience. Words are plentiful, amplified by digital platforms, but rarely backed by deeds. Social networks overflow with declarations, outrage, and posturing, but few are willing to risk even minor discomfort to live out the beliefs they proclaim. Mishima would have recognized this as the ultimate sign of decadence: a society where everything is said, but nothing is done. To him, such a culture would not be alive but already spiritually dead.

Another sharp contrast lies in the treatment of the body and the spirit. Mishima believed in forging the body into a disciplined vessel of the soul. He trained obsessively, sculpting himself as a living testament to the ideals he wrote about. Today, the body is often treated not as a vessel of discipline but as a canvas for indulgence or an object of neglect. Health is commercialized through fads, fitness commodified into trends, and discipline replaced by fleeting convenience. Where Mishima saw the body as sacred, we see it as a tool for consumption, another arena where conviction has been replaced by marketing.

Equally stark is the contrast in how society treats death and sacrifice. For Mishima, death was not something to be feared or avoided at all costs; it was the ultimate expression of meaning. His philosophy drew from the samurai tradition that saw death as a way to preserve honor and coherence. In contrast, modern society views death only as failure, tragedy, or inconvenience. We live as though survival itself were the highest goal, regardless of the quality or dignity of that life. The very idea of dying for one’s principles is alien to us, something to be ridiculed rather than respected. Mishima’s willingness to embrace death as part of life highlights how far we have drifted from the notion that sacrifice is sometimes necessary to preserve what we claim to value.

Perhaps the most telling difference is in the realm of critical thinking. Mishima’s works, however unsettling, were an attempt to confront his era with uncomfortable truths. He criticized consumerism, pacifism, and the decay of tradition not because it was popular, but because he believed it was true. Today, critical thinking is often suppressed, drowned under slogans, mass conformity, or fear of social reprisal. The dominant ethic is one of compliance, a culture where dissent is punished and where the appearance of agreement matters more than genuine conviction. In such an environment, Mishima’s insistence on living authentically, no matter the cost, feels both shocking and refreshing.

This is not to say that Mishima’s ideals should be adopted wholesale. His politics were extreme, his nationalism controversial, and his methods violent. But the value of his example lies not in agreement but in contrast. He forces us to ask whether our own values are anything more than conveniences. He compels us to confront the uncomfortable truth that convictions without sacrifice are illusions, and that a society that suppresses dissent and worships comfort is a society that risks hollowing itself out from within.

In our age, discipline is mocked, conviction is treated as fanaticism, and sacrifice is seen as folly. Against this backdrop, Mishima’s life appears almost otherworldly, a relic from a past where principles were lived, not just spoken. And yet, his story is not only a historical curiosity. It is a challenge, a mirror held up to us. Do we live with the kind of coherence between word and deed that he demanded, or are we content to live fragmented lives, rich in comfort but poor in meaning? Mishima’s example forces us to ask whether we have traded honor for convenience, and if so, what that trade has truly cost us.

The value of conviction

In the end, Yukio Mishima’s story is not merely the tale of a writer or a radical, but of a man who insisted on living without compromise. His novels dissected the beauty and futility of existence, his body became a sculpture of discipline, his politics a cry for a return to honor, and his death a final act of coherence. To agree or disagree with his ideals is almost secondary. What matters is that he embodied what so few dare to attempt: a life in which word and deed were inseparable, in which conviction was not bent to convenience, and in which sacrifice was seen not as madness but as the truest measure of belief.

Mishima stands as a paradox. He lived in the modern world, publishing in international markets, posing for photographs, aware of his celebrity. Yet he rejected the very foundations of modernity, comfort, compromise, consumerism. He was a man caught between eras, carrying the weight of a samurai spirit into a society that no longer believed in such things. His tragedy is that his ideals were too much for his age; his triumph is that he refused to abandon them. By dying as he did, he ensured that his philosophy could never be dismissed as mere rhetoric. It became inseparable from his flesh, written into history with his own blood.

For us, in a time defined by moral relativism, apathy, and the suppression of critical thought, Mishima is both a warning and a challenge. A warning, because conviction taken to extremes can lead to violence and destruction. But a challenge, because the absence of conviction leads to a different kind of destruction, the slow decay of societies that no longer believe in anything beyond comfort and survival. Mishima reminds us that beliefs matter only if we are willing to bear their cost. To declare principles without sacrifice is hypocrisy; to seek beauty without discipline is vanity; to live without honor is to live without meaning.

We may not embrace his politics, nor share his nationalism, nor wish to follow his path. But we can still draw from him the enduring truth that a life without conviction is a life adrift. His example forces us to ask the questions we so often avoid: What do we truly stand for? What values would we defend even at great cost? Are our principles real, or are they just words we repeat until they no longer inconvenience us?

Yukio Mishima’s legacy is not in the specifics of his ideology, but in the coherence of his life. He refused to separate thought from action, art from body, belief from sacrifice. In doing so, he left behind not only his novels, but a philosophy lived to its absolute end. And in an era like ours, dominated by indulgence, by convenience, by fear of discomfort, his story echoes all the louder, daring us to consider whether we too have lost the courage to live and die by what we claim to believe.

As Mishima himself once wrote:

“Perfect purity is possible if you turn your life into a line of poetry written with a splash of blood.”