The forgotten libraries of the world: how lost knowledge shaped civilization

by Kai Ochsen

We tend to think of history as an uninterrupted march forward, a steady accumulation of discoveries, inventions, and ideas. Yet behind this comforting narrative lies a darker truth: human knowledge has always been as fragile as the societies that carried it. For every manuscript copied, for every idea preserved, countless others have been burned, buried, or simply forgotten. Civilization is built not only on what we know, but also on the immeasurable weight of what we have lost.

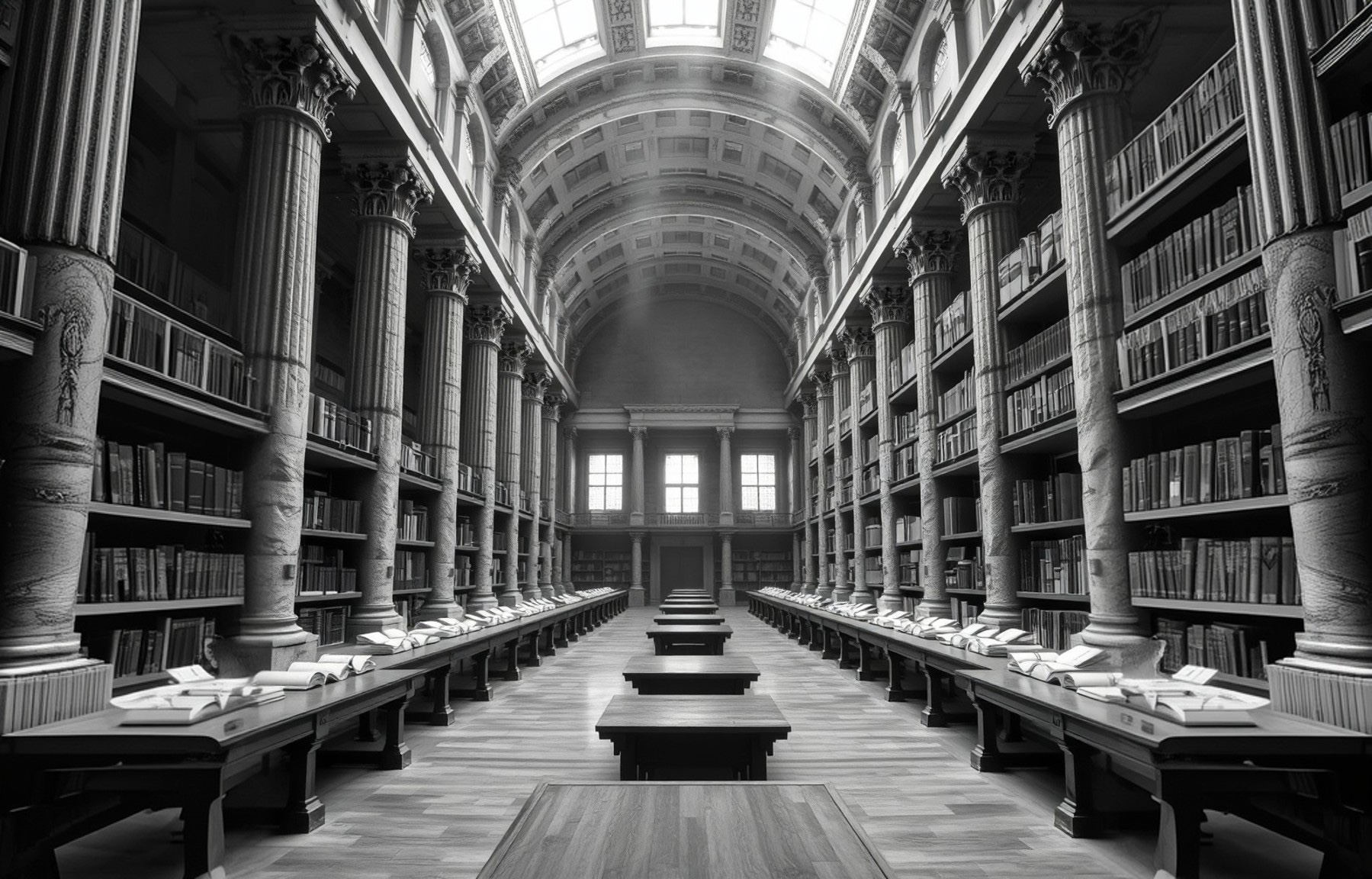

Few images capture this fragility more vividly than the destruction of libraries. A library is more than a building; it is a repository of human memory, a fragile network of scrolls, books, and manuscripts where generations distilled their understanding of the world. When a library burns, the flames consume more than paper. They erase centuries of effort, silence voices that can never be heard again, and alter the trajectory of cultures that depended on that knowledge.

Consider the myths surrounding the Library of Alexandria. Even if its destruction has been embellished by legend, the image of scrolls curling into smoke still haunts us. It has become a symbol of what happens when the guardians of knowledge falter, whether through war, neglect, or zealotry. The idea that a single fire could have delayed human progress by centuries may be simplistic, but it points to a truth: knowledge lost is not easily regained, and some of it may be gone forever.

And Alexandria was not alone. Across the world, libraries rose and fell like the empires that built them. The Buddhist monastery of Nalanda in India, where thousands of monks once studied philosophy, medicine, and astronomy, was reduced to ashes by invaders in the 12th century. The House of Wisdom in Baghdad, the beating heart of the Islamic Golden Age, was destroyed when the Mongols swept into the city in 1258, its texts dumped into the Tigris. The Mayan codices, holding secrets of astronomy and ritual, were burned by Spanish friars who saw them as pagan. Each loss was not just the end of books, but of possibilities, branches of knowledge that could have taken humanity in different directions.

Even when libraries were not deliberately burned, they often perished through neglect or politics. Monastic libraries in Europe were dismantled when kings dissolved religious orders, manuscripts scattered or destroyed for their parchment. Timbuktu’s priceless manuscripts, written in Arabic and African languages, lay hidden for centuries and nearly vanished again under modern extremism. The pattern repeats: knowledge is always one war, one fire, one ideology away from disappearing.

What makes these losses especially tragic is that they were often preventable. Books do not burn themselves. Knowledge does not erase itself. Behind each catastrophe is human action, greed, fear, conquest, or dogma. And yet, in some cases, human courage has also ensured survival: scholars who smuggled manuscripts, communities who buried codices, archivists who risked their lives to save collections. The fate of knowledge has always been intertwined with the choices of individuals.

In today’s world of digital storage and cloud archives, it is tempting to believe we are safe from such erasures. Yet the digital age introduces its own fragility. Servers can crash, formats can become obsolete, companies can disappear, and censorship can wipe out decades of work with a keystroke. What happened to scrolls and manuscripts in the past could easily happen to gigabytes and terabytes in the present. The illusion of permanence is one of the most dangerous myths of modernity.

To study forgotten libraries, then, is not an exercise in nostalgia. It is a mirror, reflecting back the fragility of our own systems of memory. The ruins of Alexandria, Nalanda, or Baghdad whisper to us that knowledge is never safe, that human progress is not guaranteed, and that what we lose shapes us as much as what we keep. To forget this lesson is to risk repeating it.

The Library of Alexandria

No lost library has captured the imagination of the world quite like the Library of Alexandria. It has become a cultural symbol, almost a myth in itself, the image of scrolls piled high, flames devouring shelves, and centuries of wisdom vanishing in smoke. Whether this vision is historically accurate matters less than what it represents: the collective awareness that knowledge, once destroyed, can alter the course of civilization.

Founded in the 3rd century BCE under the Ptolemaic dynasty, the library was part of a larger institution known as the Mouseion, a research center dedicated to the Muses. Its ambition was nothing less than to gather all the world’s knowledge in one place. Ships docking in Alexandria were said to have their manuscripts seized, copied, and stored. Scholars from Greece, Egypt, India, and Mesopotamia converged there, making it one of the earliest true centers of global intellectual exchange. It was not only a library but a dream of universal knowledge, centuries before the internet promised something similar.

What exactly was lost, however, is still debated. Ancient sources differ on the size of the collection, with estimates ranging from 40,000 to 400,000 scrolls. The content likely included works of Greek philosophy, Egyptian records, Indian mathematics, Babylonian astronomy, and medical treatises from across the known world. If even a fraction of this is true, then the library contained an unparalleled concentration of ancient wisdom. Its destruction would have been nothing short of catastrophic.

The problem is that no single event neatly explains its fall. Some accounts attribute the destruction to Julius Caesar’s fire in 48 BCE, when ships in the harbor were set ablaze during battle. Others suggest it declined gradually, suffering under Emperor Aurelian’s campaigns in the 3rd century CE and later neglect under Christian and Muslim rule. Rather than a single catastrophic blaze, the library may have withered over centuries, forgotten as rulers shifted priorities. This ambiguity has only fed the myth: the image of one great fire is more dramatic than the slow erosion of care.

What is certain is that by late antiquity, the library was gone, and with it an enormous body of ancient thought. The loss is often romanticized as the reason humanity endured a “Dark Age”, but this oversimplifies history. Still, it is undeniable that the absence of these texts delayed scientific and philosophical development. Imagine if advanced Indian mathematics or Chinese innovations had been transmitted earlier through Alexandria. Would humanity have reached modernity centuries ahead of schedule? The what-ifs remain tantalizing.

The fate of Alexandria also speaks to the politics of knowledge. A library of such ambition required state funding and protection, but knowledge has always been subject to the whims of power. When rulers lost interest or saw no political advantage in maintaining it, the library became vulnerable. The same pattern has repeated across history: when knowledge ceases to serve power, it risks being discarded.

Yet perhaps the most important lesson of Alexandria is psychological. Its story endures not because we know exactly what was lost, but because we fear the idea of loss itself. The library has become a metaphor for fragility, a reminder that human brilliance can vanish overnight. Every book we write, every archive we build, is haunted by the image of scrolls burning in Alexandria. The myth endures because it warns us of our own vulnerability.

Alexandria may never be reconstructed, but its shadow lingers in every university, archive, and digital database. The dream of universal knowledge did not die completely; it resurfaced in Renaissance humanism, Enlightenment encyclopedias, and now in the global digital network. But the story of Alexandria is always there, whispering that even the grandest collections can fall, and that the price of neglect or violence is not just material loss but a wound in the memory of humanity.

Nalanda

If Alexandria embodies the Western imagination of lost knowledge, Nalanda represents its Eastern counterpart, a monumental seat of learning in India whose destruction in the 12th century remains one of history’s great cultural tragedies. Unlike Alexandria, which we know mostly through myth, Nalanda’s existence is richly documented. For nearly 700 years, it was a thriving center of Buddhist philosophy, science, and culture, drawing students and teachers from across Asia. Its fall was not a single fire in a harbor, but a calculated act of conquest that left ashes where once ideas flourished.

Established in the 5th century CE under the Gupta Empire, Nalanda University became the most important intellectual hub in the Buddhist world. Its campus stretched across several monasteries, temples, and classrooms, accommodating thousands of monks and students. Accounts by Chinese pilgrims like Xuanzang in the 7th century describe a vast library, with nine million manuscripts housed in three great buildings. These texts covered not only Buddhist scriptures but also works in astronomy, medicine, mathematics, and logic, making Nalanda a true university in the modern sense.

What made Nalanda unique was not just the scale of its library, but its role as a crossroads of knowledge. Scholars came from China, Tibet, Korea, and even distant lands like Sumatra. The intellectual exchanges at Nalanda shaped the development of Buddhist thought across Asia, transmitting philosophies and techniques that remain central in many traditions today. It was not just a repository of texts but a living organism of teaching, debate, and discovery.

Its destruction, however, was swift and devastating. In the late 12th century, the armies of Bakhtiyar Khilji, a Turkic military general, swept through northern India. Seeing Nalanda as a symbol of Buddhist influence and wealth, his forces burned its monasteries and libraries. Accounts suggest that the manuscripts were so numerous that they smoldered for months. Whether this detail is exaggerated or not, the impact was clear: centuries of accumulated wisdom vanished, and with it, the cultural heartbeat of Buddhist India.

The consequences were profound. Nalanda’s fall accelerated the decline of Buddhism in India, which had already been overshadowed by Hindu traditions and later faced pressures from Islamic expansion. The loss of its manuscripts also meant that future generations were deprived of unique insights into science, medicine, and philosophy that may never be recovered. Unlike Alexandria, where fragments of works survived in copies, Nalanda’s destruction left almost nothing behind. What knowledge might have reshaped medicine or mathematics in Asia disappeared into smoke.

Yet even in tragedy, Nalanda’s memory survived. Its influence persisted through the scholars who studied there and carried its teachings abroad. Tibetan Buddhism, for instance, was deeply shaped by Nalanda-trained masters. In this sense, Nalanda’s destruction did not completely erase its legacy; it scattered it, leaving traces that would endure in unexpected places. This diffusion is a reminder that knowledge, while fragile in material form, can sometimes survive in the minds and practices of people.

Today, the ruins of Nalanda are a UNESCO World Heritage site, and efforts have been made to revive its spirit through the establishment of a modern Nalanda University. The initiative is symbolic, for no reconstruction can restore the manuscripts burned centuries ago. Still, the attempt reflects humanity’s enduring desire to reclaim what was lost and to resist the silence imposed by history.

The story of Nalanda teaches us that libraries are not just about storing texts; they are about sustaining civilizations. When Nalanda fell, it was not only scrolls and books that were destroyed. A continuum of learning, a living conversation across cultures and centuries, was abruptly severed. Its ashes remind us that progress is never guaranteed, and that the guardianship of knowledge requires vigilance against the forces that would erase it.

The House of Wisdom in Baghdad

In the heart of Baghdad, during the height of the Abbasid Caliphate, stood one of the most remarkable institutions of human history: the Bayt al-Hikma, or House of Wisdom. Founded in the 8th century and flourishing under Caliph al-Ma'mun in the 9th, it became the beating heart of the Islamic Golden Age, a place where translation, science, and philosophy converged. If Alexandria was the dream of universal knowledge in antiquity, the House of Wisdom was its rebirth in the medieval world. Its destruction in the 13th century by the Mongols stands as one of history’s most haunting cultural losses.

The House of Wisdom was not merely a library. It was a research institution, translation hub, and intellectual laboratory. Texts from Greece, Persia, India, and China were gathered and translated into Arabic, creating a corpus of knowledge unparalleled in its scope. Greek philosophy, Indian mathematics, and Persian astronomy found a new home in Baghdad, where scholars refined, debated, and expanded upon them. It was in this environment that algebra was formalized, astronomical models improved, and advances in medicine written that would circulate through Europe centuries later.

The scholars of Baghdad did not simply preserve knowledge, they transformed it. Figures like Al-Khwarizmi, whose works gave us the term “algorithm”, and Hunayn ibn Ishaq, who translated Galen and Hippocrates, represent the intellectual vigor of the House of Wisdom. These were not passive custodians but active creators, laying the groundwork for disciplines that remain central today. The library and its scholars embodied the idea that knowledge is cumulative and global, enriched by the contributions of many civilizations.

Yet in 1258, this brilliant chapter came to a violent end. The Mongol forces under Hulagu Khan invaded Baghdad, breaching its walls after a prolonged siege. What followed was a massacre that decimated the city’s population and infrastructure. The House of Wisdom, along with countless other treasures, was destroyed. Chroniclers describe the Tigris River running black with the ink of manuscripts and red with blood. Whether literal or symbolic, the image captures the immensity of the loss: an entire city of knowledge extinguished in a matter of days.

The destruction of the House of Wisdom did more than erase books. It marked a turning point in the trajectory of Islamic civilization. While knowledge continued in other centers like Cairo and Damascus, the momentum of the Abbasid intellectual flowering was broken. Many argue that this rupture delayed scientific progress across the region, cutting short a golden age whose potential was never fully realized. The question lingers: had the House of Wisdom survived, would the Renaissance have arrived earlier, fueled not only by rediscovered Greek texts but also by uninterrupted Islamic scholarship?

The story also underscores the vulnerability of knowledge to geopolitical violence. Libraries and scholars depend on stability; without it, even the most advanced institutions collapse. The Mongol invasion was not aimed at erasing science or philosophy specifically, but the destruction of Baghdad inadvertently became one of the most devastating intellectual setbacks in history. Knowledge was collateral damage, showing how fragile even the greatest centers of learning can be when caught in the machinery of war.

Today, the House of Wisdom remains more symbol than memory. Few physical remnants exist, and much of what it produced survived only through scattered translations carried westward into Europe. The irony is profound: the same works that were nearly lost forever helped ignite the European Renaissance. Baghdad’s loss became Europe’s gain, another reminder of how unevenly knowledge flows when war and conquest dictate its survival.

The House of Wisdom, like Alexandria and Nalanda, reveals a recurring truth: the centers of knowledge that shine brightest are often the most vulnerable. Their brilliance makes them targets, whether for conquerors, zealots, or simply the apathy of later generations. To honor their memory is to recognize both the heights humanity can reach and the depths it can fall when wisdom is abandoned to violence.

The libraries of Timbuktu

When people hear the name Timbuktu, they often think of it as a metaphor for remoteness, a place at the edge of the world. Yet in the 15th and 16th centuries, Timbuktu was anything but peripheral. It was a flourishing hub of trade, scholarship, and culture in West Africa, home to thousands of manuscripts that recorded everything from theology and law to medicine, astronomy, and poetry. Its libraries, though less well known than Alexandria or Baghdad, are among the most remarkable examples of human knowledge nearly lost to time.

The rise of Timbuktu as an intellectual center coincided with the prosperity of the Mali and Songhai Empires, when trans-Saharan trade routes carried not only gold and salt but also ideas. Scholars gathered in the city’s mosques and private libraries, producing and preserving manuscripts in Arabic and African languages. Families often kept collections for generations, treating them as treasures that defined their identity and prestige. By some estimates, more than 700,000 manuscripts existed across the region, making Timbuktu one of the richest repositories of African knowledge.

The subjects covered in these texts challenge stereotypes of Africa as a continent without written history. They include treatises on mathematics, medicine, geography, jurisprudence, and philosophy, revealing a sophisticated intellectual tradition. Timbuktu’s scholars debated ethics, documented medical practices, and recorded astronomical observations that connected them to global currents of thought. These manuscripts prove that Africa was never isolated from the great conversations of humanity; it was an active participant in shaping them.

But like so many libraries before them, Timbuktu’s collections faced threats. In the late 16th century, Moroccan forces invaded, disrupting the city’s stability. Over time, colonialism, poverty, and neglect further endangered the manuscripts. Many were hidden in trunks or buried underground to avoid looting, surviving not because of institutional protection but because of the determination of local families. Knowledge endured in fragile secrecy, waiting for rediscovery.

The most recent danger came in 2012, when Islamist militants affiliated with al-Qaeda occupied Timbuktu. Viewing the manuscripts as heretical, they threatened to destroy them. In an extraordinary act of resistance, local scholars and citizens organized a clandestine effort to smuggle hundreds of thousands of manuscripts out of the city. Hidden in metal boxes, donkey carts, and boats along the Niger River, the manuscripts were evacuated to safety in Bamako, Mali’s capital. This operation stands as one of the great modern rescues of cultural heritage.

The Timbuktu manuscripts are not relics of the past alone; they are living reminders of Africa’s intellectual contributions. Yet they also highlight the fragility of heritage. Many remain at risk due to poor storage conditions, lack of funding, and ongoing instability in the region. International organizations have stepped in to help with preservation, but the work is slow and costly. Each manuscript saved is a victory against the forces of erasure, yet each one lost is a wound to memory.

What makes Timbuktu’s story unique is the role of ordinary people in preservation. Unlike Alexandria or Baghdad, where state institutions collapsed, Timbuktu’s knowledge survived because families valued their manuscripts as part of their identity. It is a reminder that the guardianship of knowledge does not always rest with governments or empires; sometimes it depends on the courage of individuals who refuse to let their history be erased.

Timbuktu’s libraries challenge the way we think about forgotten knowledge. They remind us that history is not only about what was lost but also about what was saved, sometimes against overwhelming odds. In the dusty manuscripts of West Africa, we glimpse both the vulnerability and resilience of human memory. Timbuktu teaches us that even at the so-called “edge of the world”, knowledge has always been at the center of civilization.

Pre-Columbian codices

On the other side of the Atlantic, far from Alexandria, Nalanda, or Baghdad, another great tragedy unfolded with the arrival of European conquistadors in the Americas. The civilizations of the Maya, Aztec, and Mixtec had long traditions of writing, recorded in intricate codices painted on bark paper or deerskin. These manuscripts contained histories, calendars, astronomical knowledge, religious rituals, and genealogies. They were not books in the Western sense but richly symbolic documents that carried the collective memory of entire cultures. The vast majority of them were burned within a few decades of European conquest.

For the Maya in particular, writing was central to their civilization. Their hieroglyphic system was one of the most sophisticated in the pre-Columbian world, capable of recording not only dates and names but also complex narratives. Codices were used to track celestial cycles, agricultural rituals, and dynastic histories. The destruction of these works was not just a material loss; it was an obliteration of a worldview that linked the heavens, earth, and society into a unified system of meaning.

The most infamous event occurred in 1562, when Diego de Landa, a Franciscan friar in Yucatán, ordered the burning of dozens of Maya codices and thousands of idols, declaring them works of the devil. His justification was religious, but the act was also deeply political: to erase the spiritual foundations of Maya culture and replace them with Christianity. In a single day, centuries of knowledge about astronomy, medicine, and ritual were reduced to ash. De Landa later wrote a detailed account of Maya customs, ironically, one of the few sources that preserved fragments of what he had destroyed.

For the Aztecs and Mixtecs, the story was similar. Their pictorial codices documented migrations, conquests, and sacred rituals. Spanish conquistadors and missionaries destroyed most of them, seeing in their symbols a threat to colonial authority. Today, only a handful of Aztec and Mixtec codices survive, often preserved in European collections. They offer tantalizing glimpses into a lost world, but they are fragments of what must once have been an immense and complex literary tradition.

The loss of the codices had profound consequences. Without them, indigenous peoples were stripped of their historical continuity. Their calendars, myths, and scientific observations were replaced by European narratives of conquest. Knowledge that had been refined for centuries, agricultural cycles tied to astronomy, herbal medicine, and intricate political systems, vanished. Colonization was not only territorial but also epistemic, replacing one body of knowledge with another and leaving future generations with a distorted sense of their own past.

And yet, as with Timbuktu, resilience emerged. Some codices were hidden and rediscovered centuries later. Oral traditions preserved fragments of mythology and ritual, passed down through storytelling. In recent decades, scholars and indigenous communities have worked to reconstruct and reinterpret what remains, using archaeology and linguistics to breathe life back into a culture nearly silenced. Still, the enormity of what was lost cannot be overstated. Imagine how differently we might understand the Americas if thousands of codices had survived.

The burning of the codices illustrates a recurring theme: the destruction of knowledge as an act of domination. Conquerors often believe that erasing the past is necessary to secure control over the future. By eliminating indigenous texts, the Spanish sought to erase memory itself, replacing it with their own narratives of salvation and conquest. The result is a wound that still shapes the cultural identity of the Americas today.

The codices remind us that knowledge can be annihilated not only by fire and conquest but also by ideology. When texts are deemed dangerous simply because they tell a different story, the result is cultural amnesia. The ashes of Maya and Aztec libraries are not just remnants of a lost past; they are warnings of how fragile truth can be when power decides what deserves to survive.

Europe’s forgotten monastic libraries

In Europe, the fate of knowledge was not decided only by invading armies or foreign conquest. Often, it was internal upheaval, politics, and religious reform that determined which texts survived and which were erased. The monastic libraries that once dotted the continent illustrate this perfectly. For centuries, monasteries were the keepers of Europe’s written memory, copying manuscripts in scriptoria and preserving works from antiquity. Yet these same repositories of wisdom were also highly vulnerable, and many disappeared not in flames but in waves of reform and dissolution.

During the early Middle Ages, monasteries became the principal centers of learning in Europe. While political authority fragmented after the fall of Rome, monastic orders sustained the fragile thread of literacy. The copying of manuscripts in Latin preserved not only Christian scriptures but also fragments of Greek and Roman literature, philosophy, and science. Without them, works of Aristotle, Virgil, or Cicero might never have reached the Renaissance. These libraries were small compared to Alexandria or Nalanda, but they were lifelines of continuity in a world often descending into chaos.

However, preservation was selective. Monks copied texts they considered valuable or safe, leaving others to vanish. Entire traditions of pagan philosophy, heretical gospels, or alternative sciences were excluded and eventually lost. Thus, the monastic libraries did not merely preserve knowledge, they also shaped it, determining which voices echoed into the future and which were silenced. Their shelves reflected theology as much as scholarship, and this bias profoundly influenced the European intellectual heritage.

The most devastating blow came later, during the Reformation and the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century. In England, Henry VIII’s break with Rome led to the systematic closure of monasteries, with libraries looted, sold, or destroyed. Thousands of manuscripts were lost in this process, not through war but through deliberate policy. Some were recycled for their parchment, scraped clean to make new documents, while others were left to decay. The treasures of centuries became casualties of political ambition and religious reform.

Elsewhere in Europe, similar processes unfolded. The Thirty Years’ War in the 17th century saw libraries plundered as spoils of conflict. Even outside wartime, secularization and modernization often regarded monastic collections as obsolete, leading to neglect or dispersal. The irony is that while monasteries had kept knowledge alive through centuries of turmoil, they became victims of the very modernization they had helped enable.

Yet not all was lost. Some manuscripts escaped destruction by entering royal or university collections, where they laid the foundations for modern libraries like the British Library or the Bibliothèque nationale de France. The survival of these texts, however partial, fed the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and modern scholarship. But the cost of what was lost remains incalculable. How many alternative histories, forgotten philosophies, or local traditions perished when monastic shelves were emptied?

The story of Europe’s monastic libraries highlights an uncomfortable truth: the guardians of knowledge can also be its censors. Their choices, whether guided by faith, politics, or convenience, shaped the intellectual trajectory of Europe as much as the texts they preserved. What we call “Western civilization” is built not only on the continuity of ideas but also on the silence left by deliberate omissions.

Today, the ruins of monasteries and their scattered manuscripts serve as reminders of both resilience and fragility. They testify to centuries of devotion to learning, but also to how easily memory can be sacrificed to reform or ambition. Europe’s forgotten libraries were not destroyed by outsiders but by decisions from within, a sobering reminder that the greatest threats to knowledge often come not from enemies, but from ourselves.

Modern losses of knowledge

The destruction of libraries is not only an ancient tragedy. Even in modern times, humanity has repeatedly witnessed the erasure of knowledge, proving that our memory remains as fragile as ever. Fires, wars, and even digital collapse remind us that the guardianship of knowledge is never complete. Each generation faces its own moments of loss, sometimes sudden, sometimes gradual, but always irreversible.

One of the most infamous modern examples is the burning of the Library of Sarajevo in 1992 during the Bosnian War. The Vijecnica, Sarajevo’s National and University Library, was shelled, and nearly two million books and manuscripts were destroyed in the flames. Images of charred pages fluttering through the streets shocked the world, echoing Alexandria’s myth in real time. The deliberate targeting of a library in the late 20th century exposed a chilling truth: even in an age of international law and human rights, cultural destruction remains a weapon of war.

The Second World War had already demonstrated this on a massive scale. Libraries across Europe were bombed, looted, or burned. The Warsaw Public Library and the National Library of Germany in Berlin suffered devastating losses, while countless university collections disappeared. In some cases, the destruction was intentional, part of Nazi attempts to erase Jewish culture through book burnings and confiscation. In others, it was collateral damage of total war. Either way, the result was the same: centuries of scholarship and cultural memory vanished.

Nor are these losses confined to war. Fires in modern archives and museums have claimed vast amounts of knowledge. The 2018 fire at Brazil’s National Museum destroyed 90% of its collection, including priceless artifacts of indigenous cultures and natural history. In 1986, a fire at the Los Angeles Public Library consumed 400,000 books. These tragedies reveal that negligence, underfunding, or poor infrastructure can be as destructive as bombs. Libraries may no longer rely on parchment, but paper burns just as easily, and digital storage introduces new vulnerabilities.

The digital age brings its own paradox. On one hand, we can back up information infinitely, duplicating files across servers worldwide. On the other, we are more dependent than ever on fragile infrastructures. A server crash, cyberattack, or corporate shutdown can erase entire archives with the press of a key. Consider how many websites, forums, or digital libraries have already vanished because platforms went offline or formats became obsolete. Digital amnesia is no less real than the amnesia caused by fire.

Censorship also takes a modern form. States and corporations now possess the ability to erase or manipulate digital records on a scale unimaginable in the past. A book burned in Alexandria was gone for good, but its destruction was visible. A file deleted or altered online may vanish silently, without witnesses. The power to control memory has never been greater, and the danger lies not only in sudden destruction but in gradual, invisible erasure.

Even well-intentioned projects can fail. Think of digital preservation efforts that rely on specific software or file formats. If these technologies become obsolete, entire collections may be unreadable in the future. We may discover that our age, far from being the most secure, is one of the most precarious, where the abundance of data masks its fragility. What use are billions of files if no one can access them in a century’s time?

Modern losses remind us that the story of forgotten libraries is not just about the past. It is a continuous process, shaped by war, ideology, negligence, and technology. The fluttering ashes of Sarajevo, the melted artifacts of Rio de Janeiro, the vanished forums of the early internet, all echo the same warning: knowledge survives only if we actively protect it. The responsibility is ours, and the consequences of failure are as severe today as they were in Alexandria or Nalanda.

Guardians of knowledge in the digital age

For every fire, every invasion, and every act of censorship that has erased human memory, there have also been acts of preservation. While history often emphasizes loss, the present offers a new chapter in the struggle: efforts to safeguard knowledge for the future through digital archives and open access initiatives. Unlike the fragile scrolls of Alexandria or the manuscripts of Timbuktu, today’s repositories are not housed in stone buildings alone but in servers, networks, and cloud systems spread across the globe. Yet their mission remains the same: to ensure that knowledge endures beyond the lifespan of its creators.

One of the earliest and most visionary projects is Project Gutenberg, founded in 1971 by Michael Hart. At a time when computers were still rare and the internet had not yet reached the public, Hart had a radical idea: to digitize texts in the public domain and make them available to everyone for free. The project began modestly, with Hart manually typing the U.S. Declaration of Independence, but it has since grown into a vast digital library of over 70,000 works. Its significance is not only in the texts it preserves but in the philosophy it embodies: knowledge should not be locked behind institutions or scarcity; it should flow freely across borders and generations.

Equally ambitious, though on a different scale, is the Internet Archive, founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle. While Gutenberg focuses on books, the Internet Archive seeks to preserve almost everything: websites, audio recordings, films, software, and even social media. Its Wayback Machine, which stores snapshots of websites across time, is perhaps the closest thing we have to a time machine for digital culture. At a moment when websites vanish or are rewritten overnight, the Internet Archive provides continuity, ensuring that the digital age does not fall victim to its own impermanence.

These initiatives represent a new kind of guardianship. Where ancient libraries relied on scribes and scholars, modern archives rely on programmers, servers, and volunteers scattered across the world. They face new challenges: copyright restrictions, funding shortages, and political pressure. In some cases, corporations and governments have attempted to curtail access or remove content, raising the question of whether digital preservation can ever be fully neutral. The Internet Archive, for example, has faced lawsuits for making scanned books widely available, highlighting the tension between preservation and commercial interests.

Yet despite these challenges, such projects demonstrate an extraordinary resilience. They operate on the principle that the future of knowledge cannot be left to chance, that proactive effort is required to resist the silent erasure of memory. They remind us that preservation is not merely about nostalgia but about empowerment: ensuring that future generations can learn from the past without depending solely on the narratives of power.

Importantly, these digital efforts are not limited to the West. Across the world, initiatives are emerging to preserve endangered languages, oral histories, and indigenous knowledge in digital form. Just as Timbuktu’s manuscripts were hidden by local families, today’s communities are beginning to digitize their cultural heritage to protect it from war, climate change, or cultural homogenization. The guardianship of knowledge is becoming decentralized and global, echoing the diversity of the very cultures it seeks to preserve.

Still, digital preservation is no guarantee of permanence. Servers can fail, formats can become obsolete, and censorship can still silence. But the scale and ambition of projects like Project Gutenberg and the Internet Archive mark a profound shift: for the first time in history, humanity is attempting not only to collect but to archive the entirety of its output. It is a modern equivalent of the dream that once animated Alexandria and Baghdad, but now distributed, redundant, and, hopefully, more resilient.

The story of forgotten libraries thus acquires a new chapter. For all the losses of the past, there is also a present in which preservation is possible on a scale never before imagined. The challenge is not only technical but moral: to decide whether knowledge is to remain the guarded privilege of a few or the shared inheritance of all. The guardians of the digital age hold in their hands not just hard drives and servers but the very future of memory.

The archaeology of memory

Looking back across the long arc of forgotten libraries, I find myself haunted by the sheer fragility of memory. Civilizations have risen, flourished, and collapsed, and with them, entire worlds of thought have disappeared. The scrolls of Alexandria, the manuscripts of Nalanda, the codices of the Maya, each loss was not only cultural but existential, a reminder that our understanding of the past is always partial, always filtered through the accidents of survival. Knowledge is not inevitable. It is conditional, fragile, and deeply human.

What strikes me most is the duality: for every act of preservation, there is an act of destruction. For every scribe who copied a text with devotion, there was a conqueror or censor who erased it with fire. This tension is the archaeology of memory: history is not a smooth narrative but a battlefield, where ideas compete not only to be created but to be remembered. Our present, built on libraries both remembered and forgotten, is the product of these uneven victories and losses.

The silence of lost libraries is not empty. It is a silence filled with questions. What ideas were buried in the ashes of Baghdad? What cures or philosophies were lost at Nalanda? What cosmic patterns lay hidden in Maya astronomy, reduced to smoke in Yucatán? The absence itself becomes part of our history, shaping what we believe to be possible. We live in a world defined not only by what we know, but by what we will never know again.

And yet, within this fragility lies resilience. Timbuktu’s manuscripts hidden in wooden chests, the codices smuggled across oceans, the monks who preserved fragments of antiquity, these stories remind us that knowledge does not vanish without resistance. It survives in fragments, in memory, in oral tradition, in stubborn human defiance. The archaeology of memory is not only about ruins; it is also about survival against overwhelming odds.

When I consider the digital age, I feel the same paradox. On one hand, never before has humanity had the means to preserve so much, to duplicate and disseminate knowledge across the globe. On the other, never before has our memory been so dependent on fragile infrastructures, corporate interests, and political decisions. The Internet Archive may be our modern Alexandria, but even it is vulnerable, to lawsuits, to censorship, to the simple decay of servers. We stand at a crossroads where the dream of universal knowledge could either flourish or collapse under its own weight.

What unsettles me most is how easily we take memory for granted. We assume books will always be there, that the internet will always exist, that knowledge is permanent. History proves otherwise. Fires happen. Wars happen. Silence descends when vigilance falters. If anything, the archaeology of memory teaches us that complacency is the greatest danger of all. The moment we stop guarding our archives, we risk joining the long list of civilizations that watched their knowledge turn to ash.

Still, I do not end this reflection in despair. The very act of writing about forgotten libraries is a form of remembrance, a small resistance against silence. To remember Alexandria, Nalanda, Baghdad, Timbuktu, and the countless lesser-known archives is to acknowledge their value, even in absence. Memory, even when fractured, still carries weight. It shapes us, warns us, and inspires us to do better.

In the end, the archaeology of memory is not just about lost scrolls or burnt manuscripts. It is about us, about whether we choose to preserve, to share, to resist erasure. Our future will be judged not only by the knowledge we create but by the knowledge we protect. And perhaps the greatest tribute we can pay to the forgotten libraries of the world is to ensure that, in our time, we do not repeat their fate.